|

February 26th. Present (row-by-row from top left) Kevin McMonagle; Colin Ellwood; David Whitworth; John Chancer; Susan Raasay; Sakuntala Ramanee; Simon Usher; Julia Winwood; Valerie Gogan (not pictured)

A wonderful, deadpan subversive souffle of a play. Set in a NY hospital in which the nervous middle-aged and un-talkative Wyatt is newly arrived sharing a private room with the gregarious Budge. Wave upon wave of unexpected visitors from elsewhere in the institution – supposedly doctors, seriously ill patients - turn out to be ‘performing’ or delusional patients from the adjacent psychiatric wing. All this slowly undermine the sense of security – even the sense of underlying reality - of Budge and Wyatt, if indeed Budge and Wyatt are Budge and Wyatt. Act 2 reveals the engine room of the vertiginous deception. Actors playing lunatics, lunatics playing actors, or lunatics playing actors playing lunatics? A play that forensically disassembles apparent reality to reveal acting and its cognate performance form, madness, underneath. Underneath the apparently absurdity a gradually-revealed swiss-watch realist mechanism driving the apparent quantum warpedness. It's also full of vivid and wry characters, and of such characters playing such characters. And for an early 80s piece it impressively manages to be wonderfully evocative of millennial immersive and situationist theatre, while also satirising a certain type of very 21st Century jet-set theatre-festival-groupie, determined to track down the latest elusive hot ticket. DeLillo is clearly even more than a great novelist. On the basis of this and of his later play we read in Holborn last year – Valporiso – he is also a major playwright. As with the novels, this play both celebrates and subverts the artificiality and insubstantiality of modern life. The dialogue has a wonderful deadpan relish. Its ultimate ‘trick’ of deadpan serial and multiple un-maskings, in which each subsequent layer is presented as reality only to be then revealed as just another performance, is oddly reminiscent both in tone and technique of late-stage Ben Johnson, in his The New End for example. In terms of the theatricality and role playing you could also mention Pirandello of course. So it looks like an absurdist play until you work out the intricacies of the situational mechanism. And then it offers the satisfaction of it all fitting together. In a way it's a bit like Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, where everyone in the anarchist cell turns out to be a 'plant', so the spies are all from the same side and basically spying on each other. But with the Delillo the actors and the medics are all psychiatric patients...or the medics and the patients are all actors in the same troupe. The 'mark' Wyatt turns out to be the maddest of them all, giving in Act 2 his 'performance' as the Robin Williams-esque channel-hopping tv. A single nurse, sneaking in to 'moonlight' in the theatricals in the psychiatric patients' day room, is one genuine refugee from the supposedly 'sane' clinical world. The guy who seems unexpectedly spooked at the end of Act 1 - Budge - turns out to be (or seem to be) troupe leader Arno himself...or has taken that name (the honorary 'name' of the psychiatric ward, as well as the titular head of the theatre company...or both, or neither...). I suspect a performance would work with a kind of slightly ritualised, on-rails deadpan delivery, slightly farce-like...(with Wyatt as the Gene wilder character from The Producers and Budge/Arno as Zero Mostel.....): it's clearly not the first night of the Arno Klein after-dark production in and beyond the dayroom. They are a well-oiled machine, both in their 'doctors and nurses' schtick from Act 1 and their 'grifters' turn in Act 2. I think they do it nightly...a sop to a pretty intense narcissism, perhaps? After all in Act 2 they are fantasising their own elusive 'must see' celebrity status as the Arno Klein troupe....pursued around the world.... A great discovery, and read here with aplomb

0 Comments

February 12th. Present: Robert Lightfoot; David Whitworth; Susan Raasay; Valerie Gogan; Simon Usher; Ami Sayers; John Chancer; Paul Hamilton; Juliet Prague; Layla Jalaei

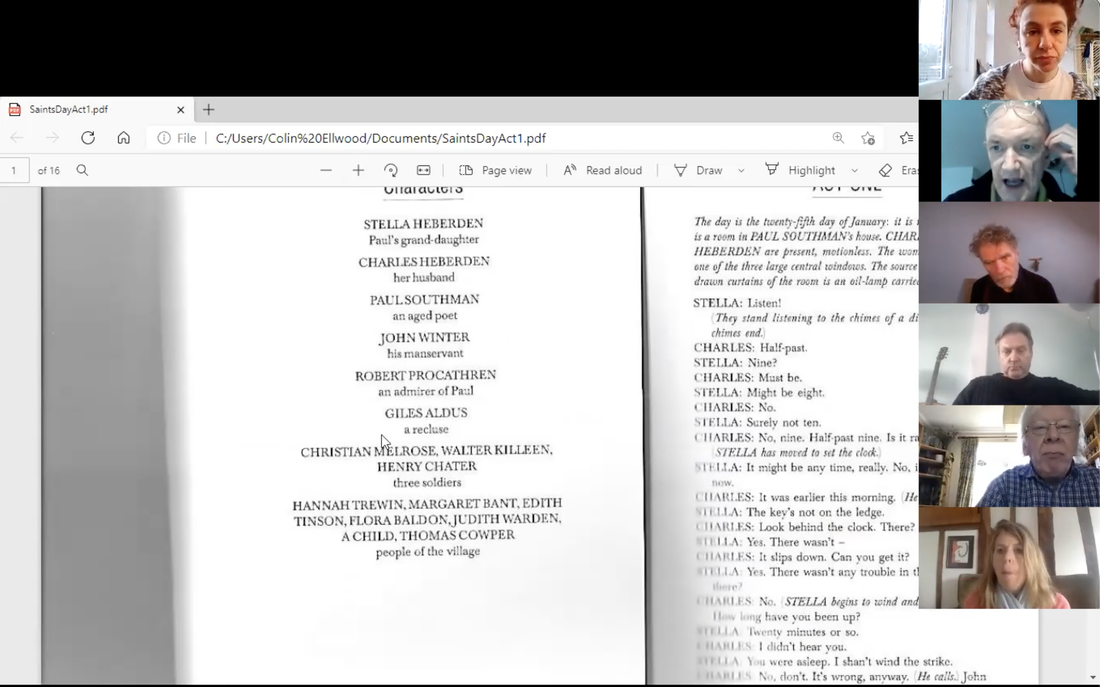

Back across the Atlantic for John Whiting's mordant 1950 Saint's Day. Agatha Christie's The Unexpected Guest meets T.S Eliot's The Family Reunion via Golding’s Lord of the Flies. A rackety and impoverished country house of resigned, retracted artists under virtual siege from a hostile village and runaway psychopathic soldiers. Subsequently a minor poet-critic runs amok having been bullied and taunted into inadvertently and randomly shooting someone through a door. In the end, the three (deserter) foot-soldiers-of-the-apocalypse, partly corralled by the now feral poet-critic, string the resident artists up on two dead Golgotha-evoking trees. Overall a brilliant excavation of the underside of Festival of Britain optimism and a foreshadowing of Pinter, David Rudkin and Lindsey Anderson. And great fun to read this psychotic, symbolist-inflected twist on the country-house drama. So…an isolated country house, inhabited by reclusive, penniless, rejected, once feted, artists overseen by an apparently senile patriarch. Then the outside world comes calling, firstly via the young critic-poet come to chaperone the patriarch to a supposedly redemptive literary dinner in London in honour of his birthday, and then ultimately in the form of three psychopathic deserting soldiers. The importunate niece of the writer-patriarch is the one who takes the random bullet; the poet-critic is bullied into a kind of savagery; and the patriarch reveals he is not quite so senile after all when given purpose in a class-war. The two original rejected artists – the old writer and a young painter who has previously retreated from London in terror at the critical world - are in the end accorded the Calvary treatment. Meanwhile the very antagonistic local village gets torched when the local vicar burns all his precious religious books in his fireplace and things get out of control. Throughout, the atmosphere is charged, strange, artificial and highly symbolic. The play reads amazingly, in a hermetically sealed sort of way - almost a guilty pleasure, if a little over-loquacious at times. Hints of Lyndsay Anderson’s If in the casual bullying meted out by the upper-classes on their perceived inferiors, and – linked to that – of early Pinter. Lots of strange names that nonetheless seem so right such as ‘Procathren’ and the inscrutable, much put-upon man-servant who is always accorded his full name when summoned: ‘John Winter’. This was Whiting’s first play. Is it in earnest or a confection, an exercise? The feel of it is more like one of those slightly psychedelic films of the 1960s. It certainly doesn’t take place in what we might take for recogniseable reality and it achieves its effect by vivid assertion rather than bottom-line plausibility. But it always seems to know where it is going and unfolds in accord with a deeply satisfying internal logic that is surprising but also, on arrival, inevitable-seeming. Yes, a confection, a brutalist dream play, but the difference between artificial confections and ‘serious’ and earnest state-of-the nation realism seems to matter less now ….just think of the dramatic worlds of Philip Ridley. This has something of the same kind of sealed, simulacrum-world quality. And it absolutely stays with you, as a siren song conjuring a flavour of right-wing conspiracy, a class-conflicted world in which affectless roundheads are presented as taking over… an enlightenment world gone rotten. In doing so it seems to predict the dark conspiracy theories and rumoured coup plots characteristic of the UK in the early seventies…. On the basis of this could you perhaps call Whiting the great lost playwright of the right? His view of human nature is dark to say the least, unalloyed, and because his action and world are so ‘unreal’ yet so well internally supported, he has the knack of creating a sense of the numinous, of offering a stark myth, an inscrutable parable relished with an underlying sense of latent violence. He died in 1963 at the age of 45. This play absolutely touches a nerve still, and here elicited some rich and wonderfully characterful readings here. Whiting’s slightly later Marching Song would be his next play to look at I think January 29th 2021: Present (from top row, left: David Whitworth; Colin Ellwood; Rob Pomfret; Valerie Gogan; Sakuntala Ramanee; Susan Raasay; Julia Winwood; Kevin Mcmonagle; Jamie Newall; Emmanuela Lia; Emily Essery; Marta Kielkowicz (not pictured); Simon Usher (not pictured)

The first of two prophetic plays from either side of WW2, each offering a compelling social metaphor for their - and perhaps our - time. Here a Broadway 1939 epic: Maxwell Anderson's Key Largo, linking Fascism in (amongst other places) the Spanish Civil War to America's own tacitly accepted free-market gangsterism, represented as a small-time huckster and his gang who've hijacked an out-of-the-way Florida Keys hotel to run a gambling racket out of. Like fascism, this operation is shown as centring on a cult of personality, absolute commitment from underlings, and tacit acceptance by the authorities. Remind you of anything/anyone at all? In the play a jaded Spanish war turncoat has a chance to redeem himself by trading in the appeasement card and standing up to the domestic US ‘proto-fascists, but at the cost of his life. An astonishingly premonitory play for 1939, let alone from Broadway, and great to get a sense of the US playwriting generation slightly after O'Neill and Odetts and before Miller and Williams, especially through a play with such colourful, noir-ish roles, if a little marinated in earnest sermonising. Maxwell Anderson also worked with Kurt Weill on September Song and whose work was also the original source of lots of British Elizabethan historical film dramas such as Fire Over England with Betty Davis. Extraordinary that this (free)-verse play lasted on Broadway in 1939 for over a hundred performances. Paul Muni and Uta Haagen took the two leads. The play was subsequently rather brutally adapted, in effect used as no more than raw material, for John Huston’s 1949 film of the same name with Bogart, Bacall and Edward G Robinson. The play takes itself very seriously, with extended speeches lamenting the death of god and the meaninglessness of the universe, all of which now feels very much like last century’s news. If the music of the piece seems at times bloated, and the pace a little waterlogged, the treatment of the Sidney Carlton-like redemption story at its centre doesn't help. It seems flat, over-explained, over-emphatic and psychologically inert and one-note. ‘King’ is the American Spanish Civil War veteran visiting the bereaved families of his comrades whom he abandoned in the field when it looked like they were on the point of being overrun by the fascists. He had been their leader and inspiration for travelling to Spain in the first place and now offers them the chance to walk away from the fighting, knowing that death was otherwise imminent and overall defeat by the fascists in any case certain. They stay on the basis that commitment to a cause – even a lost one – gives life meaning in a godless world. This episode is the play’s extended prelude, realised with a rather beautifully poignant and lyrical atmosphere. Back in the States, King becomes a bit of a hobo visiting his ex-buddies’ scattered families in an attempt at a kind of (unspecified) atonement. The last of these is to the most important to him: the sister and blind father of his erstwhile best friend ‘Victor’. If King stands up to the gangsters who've taken over their hotel, he potentially redeems himself for his Spanish ‘betrayal’. In perhaps the oddest and strangely over-emphatic plot-point, he confesses to his dead friend’s father and sister that not only did he leave his companions, but subsequently blended into and even joined the fascists in order to save his own life. As we see him King appears pathetic, guileless, depressive and generally woeful. Yet surely with a little more positivity and making more of internal contradictions this could be a really fascinating and ambiguous character. And overall this plot vector makes a fascinating link between European fascism and gangster capitalism in the US. Of course, King ultimately does stand up to the gangsters, making the ultimate sacrifice and as a result being symbolically recognised by the family as the reincarnation of their ‘son’. The gangsters are brought vividly to life by Anderson and there is some classy melodrama and emblematic plotting. And in its perceptions about the political implications of appeasement and amoral capitalism supported and sustained by a facilitating local civic regime (and strange pre-echoes of the recently ejected 45th president’s behaviours and risks) it is very telling indeed. If only it didn’t explain itself at such length, and if the psychology of King wasn’t quite so flat and miserable…But it feels that some very targeted corrective surgery by a good playwright excising the windy philosophising and tightening the screw of King's mojo might make this fascinating play very serviceable. And wonderful to hear the context for the later and livelier and more compact and punchy flourishing of Miller and Williams. The reading was inevitably long, but with some really rich and characterful voicings, especially of the gangsters. The gangster elements had slightly the feel of translations of Brecht’s Jungle of the Cities. Friday 11th December

Present (Row by row from left to right): Gwen MacKeith; Colin Ellwood; JAmie Newall; Susan Raasay; Emmanuela Lia; Adam Tyler; Simon Usher; Kevin McMonagle; Julia Winwood; David Whitworth; John Chancer; (Valerie Gogan)

A real pleasure to be reading Gwen MacKeith’s new ‘in-development’ but already very accomplished translation of eminent Argentinian playwright Griselda Gambaro’s extraordinary 2012 spin on Ibsen’s A Dolls’ House. In Dear Ibsen, I am Nora, Gambaro imagines Nora conjuring the playwright himself into her drawing room, for guidance and also to help with her growing sense of existential unease. A sharply-compressed version of the original Doll’s House action ensues, with Ibsen pretty constantly and sometimes unsettlingly in attendance advising his principal character (and occasionally the others) while also attempting to construct and manage the play in real time like a frazzled Victorian Mike Leigh operating against the clock. This clever conceit occasions both a meditation on the messy process of writing plays in general, and a probing of the politics, possibilities and prevarications of Ibsen’s classic in particular, as playwright and central character engage in a sometimes fractious dramaturgical collaboration. Gambaro also mines the socially-comedic potential of Ibsen's incongruous half-presence as an awkward middle-aged celebrity, resented and sometimes even rebuffed by his own characters. The great man is in fact presented here as a kind of evolved version of Nora’s husband Torvald who, Gambaro's conceit implies, is himself a dramatist manqué, attempting to impose an even more reductive dramatic narrative on his mercurial wife. In fact Ibsen is shown as having a strong vested interest in Torvald’s efforts, since forcing Nora into implausible genuine dolls-house infantalism at the beginning of the action (when in fact she is already very much experienced and is deftly managing a difficult reality) serves to optimise the character’s subsequently dramatic journey. In some ways Nora is here more astute than her author, sometimes lashing out in exasperation at the weaknesses of the latter’s dramatic carpentry as the play unfolds. Nora even points out the absurdity of there being so many entrances and exits in what is supposedly a private drawing room. Are these 'weaknesses' in general functions of Ibsen as an individual, or of his historical and cultural context, or simply the necessary elisions and compromises of playwriting itself, the collateral damage involved in wresting dramatic impact and meaning out of reality’s flow? Gambaro expertly keeps all these options in play. At the same time she justly honours Ibsen’s genius and his genuinely revolutionary qualities: this is very much one great dramatist hailing an honoured predecessor. There are many telling, witty and insightful moments and tropes: Ibsen shown as being ‘in process ‘(‘I don’t know yet’); his having different relationship with different characters, for example being slightly scared of Torvald, and Dr Ranke bearing a grudge against him for his dramatically-convenient fatal affliction. It is Nora's impoverished friend Christina who is depicted here as taking the initiative on Nora’s ultimate admission of 'guilt', advocating the value of pre-emptive disclosure directly against Ibsen's wishes. Gambaro also underlines Ibsen’s awareness of the financial and class constrictions in the situation as well as the gender ones. There is a telling moment when three middle-aged men – Torvald, Ranke AND Ibsen - go off to letch at Nora practising the tarantella. Gambaro at times daringly sharpens Ibsen’s dramaturgy, for example intensifying the Cristina/Nora contrast, with Cristina shown as having the courage to accept a family, just as Nora finds the the courage to reject hers. A key and hugely effective moment of silence between Christina and the blackmailing Krogstadt beautifully parallels the subsequent silence between Torvald and Nora (the former employing an emotional blackmail). The main focus throughout though is on Nora. Gambaro’s Ibsen guides her, advises her, corrects her and puts obstacles in her way as she explores dramatic solutions to her problems. In turn she questions Ibsen’s intentions for her: will she be a heroine? Commit suicide? In the end Gambaro’s Ibsen does not ‘abandon’ Nora. This is strangely moving and perhaps here there are shades of Flaubert’s ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi’. When Torvald, the apparent danger of his 'disgrace' over, offers to forgive Nora as she had hoped/fantasised, Ibsen seems conflicted. Will he settle for this more conventional ‘miraculous’ ending? In the end the playwright is shown as being redeemed by his character's unruly courage, and so it is not just Torvald’s doll’s house latter escapes, but also Ibsen’s. In the process she rejects his subsequent assertion that he created her and so should control her: She exists, she asserts, already, and with her own potential. And that of course, is partly (only) also a covert tribute to Ibsen’s greatness. In the end, after a (third great) pause/silence, Ibsen wishes her valedictory luck. And so Gambaro shows them both as pathfinders, revolutionaries. We concluded the session with a second, earlier MacKeith Gambaro translation, the beautifully ambiguous, sometimes Pinter-esque short two hander Asking too Much, astutely exploring emotional blackmail and tacit emotional support in a relationship that may or may not be ex-partners enacting a kind of covert role-play. A great coda that perfectly occasioned a kind of balanced and equal ‘round’ of partnerships for all attending Friday 4th December

Present (Row by row from top left): Simon Usher; Colin Ellwood; Emmanuela Lia; Jamie Newall; Sakuntalla Ramanee; Kevin McMonagle; Susan Raasay; Jennifer Woodward; David Whitworth

Joe Chaikin and Jean-Claude Van Italie’s 1968 Open Theater creation of an ensemble ritual, exploring the primal moment of the Genesis creation story, and where it all went wrong – or perhaps right – for humankind. Old stories Have a secret. They are a prison. Someone is locked inside them. Sometimes, when it's very quiet, I can hear him breathing' A beautiful evocation of counter-cultural innocence being 'challenged', and of the primal roots of conflict being accordingly sought, and one that imagines the 'Fall' as an ambivalent event inciting both the ‘negative’ violence of hate but also the constructive 'violence' of self-discovery and of resistance to arbitrary power; all resolved in the endless rhythm of biblical ‘begatting’ in the piece’s concluding section. Van Italie, Chaikin and their originating ensemble ask, was ‘the fall’, on balance, worth it? In contemporary (1968 American) terms, the result is shown as being a culture that is (or was) on a kind of 'life support' (the patient in the opening section having brain surgery...a shot president on life support....and then the enervated 'popular song' at the end), and that is also troubled, alienated (wonderful sections expressing troubled individual consciousnesses that apparently Van Italie adapted from testimony from ensemble members) but still potentially – in its capacity for revolution and renewal - alive. Van Italie's beautifully allusive and courageously spare text is commendable as much for what it compresses and excises, as for what it directly states. Its 'governing' structure an implying 'trace' rather than an explicit statement. An extraordinarily disciplined and tight text occasioning (in precious archive film from the original production) apparent counter-culture earnestness, but also some wonderfully specific and bold stage action. Friday 20th November

Present: (Row by row from top left, above) Susan Raasay; Colin Ellwood; Zara Tomkinson; Jamie Newall; John Chancer; Kevin McMonagle; David Whitworth; Simon Usher; Emmanuela Lia; Emily Essery; Charlotte Pyke; Valerie Gogan)

Last week, symbolism from Maeterlinck and then in the Bonhoeffer, a visit from a mysterious stranger who may or may not represent death. Here, Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea is surely a collision between symbolism and realism, with the former represented by a visit from another stranger. This time, he embodies something primal and obsessive that threatens to draw central character Ellida away from her fragile and compromised marriage back to the obsessive self-loss represented by the sea. We sampled various translations live but ended up reading the very first English, Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor's from 1890. The elegance, poise and restraint of its period-specific language balanced delicately on the shifting primal currents beneath consolidated the sense of a fragile societal containment being put under huge strain by the pull of the 'stranger' undertow: collegiate civilization and compromise versus emotional intensity and purity; the multiple versus the unitary; to extrapolate further: constitutional accommodation versus instinctual dictat/imperative; democracy versus fascism; rationality versus religious faith and absolutism. The Stranger offers Ellida certainty in submission to emotion and elemental drive; her husband Wangel on the other hand offers the maintaining of a family, the delicate accommodating of opposing needs and trajectories; love as a nurturing rather than as a demand; maternal/parental love rather than the erotic. The 'light/life' offered by Wangel is 'ethical’...but can appear ineffectual, compromised, superannuated. Overall, it's perhaps Pentheus against Dionysus; Theseus against the Minator. The play is accordingly built around two ‘vertical’ poles: on the one hand the flag raised in the garden in Act 1, which represents the compromises of nationhood and ‘rubbing along’ with unshared secrets around a common denominator, a holding mechanism, a symbol of uncertain substance. On the other hand there is the tall lean frame of the Stranger, embodying something much darker. The play is also a disquisition on art – there are at least three artists in the play – the young would-be sculptor Lyngstrand who has intuition but no sense of the commitment involved in realising it aesthetically; the local jack-of-all-trades Ballested who spreads himself and his creative efforts with farcical thinness….and then Ellida herself, yearning to be in the grip of an obsession that deprives her of choice, and through which her life will become in itself her life's artwork. She ultimately (and implausibly?) stays with her ‘civic’ family after her husband makes clear that he accepts any decision she might make. The politics and psychology of that outcome surely need more exporation than the play allows. A long play, much longer than might be thought, since the central Ellida/Stranger/Wangel action is complemented/contrasted with the tragectories of Wangel’s two daughters from his first marriage and their relationships with on-off lovers, but very rewarding especially in the immediate context of its close contemporary the Maeterlinck, and its distanct descendant the Bonhoeffer read in the previous session Fri 13th November

Present: Jamie Newall; Colin Ellwood; Sakuntalla Ramanee; Hemi Yeroham; David Whitworth; Julia Winwood; Emmanuela Lia; Marta Kielkowicz; Simon Usher; Valerie Gogan; Adam Tyler

After the epic experience of last week’s all-action Schiller, here two shorter scripts aim to fathom the boundaries of the unknown. Firstly Maurice Maeterlinck’s hugely influential Symbolist Les Aveugles (The Blind/The Sightless) from 1890, in Laurence Alma Tadema's translation from five years later. Six blind men and six blind women from an ‘asylum’ on an island wait in a forest clearing for the return of their supervising priest, only latterly to discover that his corpse has been with them all along. Read privately, the symbolism here seems crushingly obvious, but when voiced in the live session, the blind characters’ central high-stakes action of listening comes to the fore, as does the delicate balancing of the multiple ensemble roles and voices, and the imaginative and psychological logic with which the situation unfolds from its simple originating premise. The performance itself rises to meet and subsume the play’s idea/concept like a tide coming in, and it is wonderful in this reading to hear all involved easing themselves towards trust in the material; allowing rather than imposing. The text itself enacts a series of attempted ‘fathomings’ of the unknown, and the outline of this activity is – in an almost Brechtian way - thrown into stark relief by the fact that we (the audience) can ‘see’ the situational reality that the characters themselves only dimly apprehend. By motivating his characters to truly wait - at the apparent mercy of large forces held in potential that they are trying to apprehend without provoking - Maeterlinck has found the perfect engine to drive performers' sensitised stillness and economy of gesture. On the other hand what makes the play apparently so at odds with current times is its assumption that the implied death of religious authority and the accompanying metaphorical human ‘blindness/lostness’ needs in itself saying, let alone the sense that this state of affairs is profoundly tragic. What was clearly news in 1890 now surely palls in significance in light of the travails of the subsequent century and beyond. The play takes place in a lush forest, and we are now all too aware that the forest itself is under existential threat. And necessary efforts to preserve that ‘forest’ can in themselves now bestow meaning. The play’s quiescence in the face of meaninglessness then feels both self-indulgent and self-aggrandising. The Blind then marks a moment of sudden absence and withdrawal, the moment when a huge edifice – religious sensibility – has already collapsed, but before the echo of the collapse has died away. Subsequent waves of performance (after-shocks?) replay this moment of seismic crumpling as burlesqued farce (the absurdists) or (as in Beckett) as shrivelled, rigamortised formalisms; as small structures fashioned from the wreckage of the ‘temple’, through which inhabitants can occasionally peek to experience Maeterlinckian moments of universal silence, awe and terror. In that terror and awe though, there is also a beauty, an apprehension of sublimity, born of the stark and straitened earnestess of stillness and listening. And that is what the vividly imagined and rigorously developed dramatic situation of Maeterlinck’s play, if trusted and invested in by performers as here, conjures beautifully. For the second half of the session, an even greater rarity: German Lutheran theologian and pastor Deitrich Bonhoeffer’s 1942 dramatic scenes towards an unfinished play: Three extended, discursive encounters set in a small Germany town in the aftermath of World War One. The student son of the local hospital surgeon and his wife has only a year to live, having sustained serious wounds in the trenches. His parents know this and his closest friends find out through the action. He knows too, but he doesn’t know that they know. He yearns for a kind of noble acquiescence to death; for a silence to counteract the empty rhetoric of ‘freedom’ that is coming to dominate the contemporary political agenda as – implicitly – the Nazis advance. The play’s premise is that the latter have arisen as a result of a kind of ‘un-rootedness’, a lack of trust and of deep societal order. Death, and knowing how to die, is the ultimate test of authenticity, the validation of that underlying order, of the eternal loving cycle of mortal prey culled by divine ‘hunter’. As part of this cycle death is portrayed as a kind of act of love perpetrated by god. It’s a patrician and acquiescent vision, and here balances the preceding Maeterlinck in its advocacy of fatalistic acceptance of the inevitable (whereas Maeterlinck’s characters are terrified of this), but it echoes the earlier play in its recognition of the limitations of language and in its general homing in on death and silence. In the Bonhoeffer, the dying middle-class student is contrasted with a working class war-wounded boy who is by comparison ungrounded, thinking of suicide, and visited by a stranger who may or may not be death, or represent the commercialisation of death. Bonnhoeffer apparently abandoned the drama because he thought the material wasn’t ‘dramatic’, but there is something refreshing about the expansiveness and discursiveness of this, the careful setting out of fresh and thoughtful arguments that in the reading itself was hugely absorbing. And the battle between the ‘grounded’ and ‘ungrounded’ youth surely has great dramatic potential. While Maeterlinck seriously attends to the universe, Bonhoeffer attends to ideas about the universe. Chastened awe, a rare commodity in current drama, is vividly present in both. Present (from top, left to right along each row): David Whitworth; Colin Ellwood; John Chancer; Will Lewis; Rob Pomfret; Sakuntala Ramanee; Juliet Grey; Valerie Gogan/Simon Usher; Adam Tyler

Schiller’s Mary Stuart is about a woman aspiring to saintliness but beset by passion and with a diffuse sense of existential, primal guilt. Despite here making very free with history, Schiller creates a plausibly real world and the play resonates as a haunting and haunted meditation on guilt, the acts and rituals of its expiation, and on the ambiguous relationships between morality, politics and eternity. Schillers subsequent tragedy The Maid of Orleans/Joan of Arc (read on Friday 16th October) similarly features a female protagonist pulled between the sensual and the serene. Experienced here in Robert David Macdonald’s crisp translation for the Glasgow Citz from 1988, Schiller’s Joan (very unlike his conception of Mary) begins in a kind of full-throated, barrelling saintliness, fueled by faith in both the Virgin Mary and France. This has a galvanising and balming effect on her fractious fellow countrymen. But then her common humanity kicks in, and she looks down from the saintly tightrope she has so far confidently bestrid. Frozen in the twin headlights/spotlights of desire and realpolitik, and still refusing to remove her protective armour (literally and metaphorically) she wobbles and falls, her rhapsodic song of simple faith abruptly staunched. (When publically and spectacularly accused of witchcraft by her own father at the supposed moment of her triumph, she completely loses the gift of speech. Whether he is the ‘small boy’ here, she the ‘emperor’, and whether she is metaphorically ‘naked’ or ‘clothed’, is one of the playwright’s main points of exploration). Her subsequent triumph as imagined by Schiller is in her ultimate return to the saintly highwire in full knowledge of the potential consequences of the laws of human gravity, and with a willed rather than assumed clothing/armour of faith. Kierkegaard would have understood and approved of this trajectory, if not of its supposed conceptualisation as tragedy….and certainly not of the hilarious and enticingly weird ‘superwoman’ denoument of Schiller’s play, in which mighty-atom Joan leaps to simultaneous victory, vindication and death in a single bound: Saints of the (other) world, you have nothing to lose – or shatter - but your chains…. There are some great scenes in the play, such as Joan’s encounter with a mysterious black knight embodying her internal doubts, and also some great melodramatic/heroic set pieces. The psychological and situational complexity involved is mainly realised in a mythical/emblematic register (we the audience are clearly intended to think by mean of Joan and her situation, as is the case with myth, rather than empathetically with her, in accord with fully-embedded realistic situational drama). So issues such as the perils of being trapped by an unsustainable ‘celebrity’ image; the gender-identity and class disruptions (as well as the issues of faith) are all tantalisingly but rather blithely presented, as if the imperatives and temptations of spectacular stage action, set piece and meliflous, smooth, leisurely heroic verse have mulched the gritty content, just as – characteristically - the story-structure of myth takes complex situations and smooths the internal awkwardnesses off them. The play accordingly comes across as Chopin when we want Beethoven, or maybe even (I think I may have done Chopin a bit of an injustice there) as rather hollow sub-Brahms…. The set pieces are clearly contrived with melodramatic intent (the unselfconscious absurdities of Eighteenth Century heroic tragedy were of course at the time in the process of sliding towards the ‘fighting from memory’ formalism of Victorian popular melodrama…and Schiller seems here kind of caught between the two. Maybe too many drafts powered by the playwright's love of the guilty pleasures of stage gesture resulted in facile form pulverising the granular content….or (again, to suggest a more favourable perspective) is it inner complexity being externalised as positional ‘mythical’ ambivalence and ambiguity. Who knows….Staged myth is usually a lot ‘tighter’ than is the case here….it – myth – seeks to avoid the time and opportunity for too many questions to be asked of it till afterwards and outwardly. As suggested above, myth is centrifugal in its meaningfulness, realism is centripetal). Whatever, our reading on Friday generated some wonderfully engaged and richly inflected ‘soundings’ from our (in the event) unexpectedly small group (shades of Agincourt - which of course is part of the play's immediate dramatic context - in the group's rising to the many-charactered and lengthily-articulated challenges). A fascinating, if at times challenging afternoon. And that ending! Abandoning all plausibility (along with well-known historical fact) to enter the world of comic book fantasy, It is strangely effective in its shameless concept-completing, wish-fulfilling, glorious absurdity. An almost Brechtian ironic acknowledgement of the absurdity of the whole enterprise? Or a final bold and glorious endorsement of divine potency (think the chariot in Medea….)? . Maybe in a modern production, that unresolved tension would be the point… Always interesting to get a sense of what really works for the reading group and what doesn’t. What I think we need is a kind of fluent knottiness, well-placed gristle…..a balance between complex interiority on the one hand, and forward-moving fluency on the other….this Schiller tended to sacrifice the former for the latter….but then again "each experience is an arch/wherethrough gleams that untrammelled world…." Looking forward to the next one now that we are embarked on our autumn voyage. CE Present (from top, left to right along each row: Kevin McMonagle; Colin Ellwood; David Whitworth; Rob Pomfret; Michael Warburton; Simon Jaggers; Simon Usher; Julia Winwood; Emily Essery

Concluding our Summer Season supplemented by Summer Sustained (scroll down this post for accounts of that) and also as a bridge to out Autumn programme, it was a rich delight on Friday 9th October to be reading and hearing Simon Jaggers’s new play Breaking Horses with the writer present. A Faulkner-esque drama set on an a hill ‘somewhere in England’, featuring down-at-heel horseman and blacksmith Bill Brogan facing the prospect of his land being undermined – literally - by fracking, and inundated (metaphorically) by the slow-lapping tides of consumerism and suburbia. Enter his estranged half-brother Alan as the fracker’s emissary and, more sympathetically, his niece, fifteen-year-old Alice along with her almost-boyfriend Jimmy. Alice is half in love with history, tradition and ritual and very much in love with Jimmy and with Fergus. Jimmy is seventeen, disapproved of by Alice’s father, starved of affection by his own father, and about to join the army. Fergus is Brogan’s ailing old horse, very much a proxy for Brogan himself. As the frackers loom, Brogan is gearing up to put Fergus out of his misery, shooting him in strict accord with the horseman’s lore that has long insulated him against modernity and which may now in itself be a kind of madness (Brogan sustains this ideology while actually subsisting on mars bars and coleslaw illicitly scavenged from the local SPAR). Overall, the play maps the inter-generational father-son passing on of law and tradition, the fundamentally ruthless and damaging ‘breaking’ and ‘branding’ this entails and the pain it causes, and how it can be done well or badly. And, interestingly, the play's central ’shift’seems to imply the passing of this function in the contemporary world onto the female line, as if the men are becoming mere superfluous husks as the women grow in authority, confidence and expediency. That is where, if anywhere, the hope of the play seems to lie, with the ‘sap’ somehow passing to the female line. Brogan is not good at winning friends and influencing people, and he soon makes an enemy of the naïve Jimmy. Perhaps all good plays fundamentally enact a battle of inner with outer, intimacy with obviousness, and here the inner ‘glass menagerie’ of the lore of the horse offers a way of being that is felt rather than priced. Very much against the tenor of the times, the play also stands up for (old male) bastards while acknowledging their likely faults and even possibly something darker than mere ‘faults’. In doing all this it rather gloriously embraces the boldness of melodrama without ever quite falling fully into that form's overheated embrace (a delicate balance that of course Tennessee Williams - and indeed Faulkner - at their best maintained also). Some long buried secrets are revealed while others– including Brogan’s possible track record of sexual transgressions – are left tellingly unresolved; dark plots are attempted and foiled. Just when you think the play is about to settle into a relatively safe genre haven of familiar tunes, it moves up a gear to a weirder and more wonderful place in which the significance of the title becomes clear, complete with the clanking of the devil’s horse-shoe-shod foot. Will Alice herself take on Brogan’s mantle for the next generation and be able to enforce all the creative/destructive ‘breaking’ it entails? Might the play benefit from a more specific geographical/regional location? The play very much offers an imagined rather than a ‘literal’ world, but perhaps any knowledge of the actual England, and the different relations between the urban and rural environment that tend to prevail in each region, slightly undercuts a whole-hearted engagement with Jaggers’s vivid imaginative synthesis. Are we in a remote outpost, or in the garden of England? The plays epic tone, its focus on horses, together with the extreme patriarchy and the actual rural/urban relationship portrayed, even at times seem to suggests something from, say, the US Midwest. Maybe that is simply an eccentric response, but the telling influence of classic John Ford era movie ‘Westerns’ is nonetheless surely present in the play's potent, heady mix In the reading itself the actors shared and swapped roles, each drawing on their own accent and origins, creating overall a vivid mosaic of English/Scottish voices, all somehow converging and integrating at very visceral levels of experience and expression . And a good chat afterward. A great afternoon 'In a somer sesun, whon softe was the sonne I lowered me into a lockdown, as I a loon were In habite as an hermite unholy of werkes Wente I wyde though these wryghtings, wondres to here...' The Beginning - and Session 1, Thursday 9th July 2020: Participating (from the top, above, line by line from left to right) Zara Tomkinson, Colin Ellwood, Rachel Bavidge, Helen Budge, John Chancer, Susan Raasay, Marta Kielkowicz, Rob Pomfret, Ami Sayers, Simon Furness, Charlotte Pyke, Jamie Newall, Julia Winwood, Sophie Juge, Hemi Yeroham With Presence’s regular monthly ‘in-the-room’ sessions in Holborn falling victim to the lockdown (our last-scheduled such session, at the end of March, being cancelled at the last moment), and after a slightly perplexed pause, we went full-on virtual with twelve consecutive weekly zoom sessions on Friday afternoons (individual blog posts reachable from the 'March-June Blog Posts' button beneath the account of session 4 below). The basis/set-up for these sessions was the same as for the prior ‘embodied’ ones: a few days before, a general emailed invitation to the group list was sent out, with a first-come-first-served limit of approximately a dozen attendees, each self nominating without knowing the scripts to be featured and with any over-subscription offered the following week’s slot (and with a few tweaks to that model such as the tactical deployment of a random-selection ‘hat’ – actually an Indian carved box - wherever necessary). That way the accustomed, deliciously spontaneous/‘in-reading-discovery’/roles-rotating/no-prep-required effect was maintained. Typically two or three scripts featured in each session; sessions being sometimes built around a theme, sometimes not. We featured new drama, (neglected) classics, international plays and home grown. Writers and translators often attended to hear their work being ‘sounded’ (in both senses of that term). For me at least, a most rewarding aspect of this rather intense frequency and rhythm was witnessing regular participants finding their feet in the zoom format and seeing their offerings deepening, settling and enriching over time, such that they became able to ‘sit’ in an experience and to allow whatever emerged to emerge. This seemed also to have an exemplary effect on comparative new-comers, of whom there were also a good number. It felt like a culture was being created and, hopefully, curated. After twelve swiftly-sequential sessions, it also felt that we were really engaging with the plays, moments and phases of which chimed and sang. All very heartening, and we needed a break to take stock. It was the end of June, suddenly. Where next? And how for that matter, might all this feed into the renewed Presence that we are also, as a company – and as yet vaguely – intending and intuiting to 'light out' towards? Much more of that elsewhere, but that renewed ethos will it is hoped offer a range of opportunities and initiatives oriented around a shared and kindred interest in what might be termed ‘dramatic presence’: in other words in what the American Pragmatist philosopher Thomas Dewey defines as ‘experience’: basically those vertiginous shifts in sensory and cognitive ‘situated-ness’ and perception (both real and ‘imaginative/fictional’) that pretty much all performance and certainly all drama roots in and grows from: the basic human spontaneous ‘now-ness’ of ‘being’ that arises from a sudden tectonic shift in understanding and situation. These are the imaginative campfires at the centre of the forest clearings of the collective human psyche: human gathering and bonding places; offering themselves as locational and correctional signals. Plays, after all, are centrally ways of holding such energy-releasing and orientating moments in train and in tension. Presence looks for plays that offer such intensely energy-releasing moments and then harvest and meld the energy they release and inspire (from the actors) into concerted dramatic action that is richly or ambivalently - even poetically - expressed in and through (often) language. And the experience from our 12 week suggests this can to degree be achieved virtually as well (if not quite as well) as actually. And where it can be done, artists (the commonwealth of actors, writers, directors) are enthusiastic to engage with this on many different terms as long as they are terms of equivalence and as long as no one is being exploited. A resource-light levitation of, well…shared love and enthusiasm. But I partly digress Each year we normally pause the monthly reading group for July, August and early September. But this year, with the new possibilities of zoom to be explored, and enthused by the discoveries and momentum of the earlier regular weekly zoom sessions, we decided to go freeform for a summer season of occasional experiments, improvising different processes and models along the way, and also sometimes trying previously un-reachable categories of text... ...such as a t.v. script, for example. First up was a reading of regular participant Helen Budge’s new t.v. pilot Grey Collar. For this we put out a general call to the group then cast in advance from the responses (as it turned out, an almost miraculously fitting self-selection self-nominated, despite the fact that no-one knew the script or the casting breakdown in advance). No one was turned away, and everyone has substantive things to read. We approaching a couple of people to fill obvious gaps, and in the end we had two/three actors sharing the two leads, with the aim of - as we usually do - generating a variety of different possible 'takes' on each role. In addition to the pre-casting, another innovation was encouraging people to read the script in advance, while also aiming to keep things relatively fluid on the day, so that there could still be an aspect of the spontaneity that is so characteristic of Presence readings. The session itself was all we hoped for and more: stylish, confident insightful, richly textured and bold. The script came across (to me at the time and also judging by the group discussion afterwards) as deft, assured, spare, punchy and contemporary: the slow initial unfolding of a long-form modern day morality tale with a psychological mystery at its heart. The various complex strands of Helen’s intricate narrative felt beautifully ‘placed’, implacably drawing the viewer in. Also heartening were the insightful, practical, granular reflections and responses from the group afterwards. These largely centred around the import of small but vital details in key exchanges and interactions in the script: was the lead character’s boyfriend a controlling idiot, or were we just seeing him (in all-important first impressions) at a bad moment? Regarding the initial encounter between the sympathetic lead character and the Gatsby-esque antagonist, would a small change make their initial-encounter ‘snagging of fates’ more believable? Helen professed all this hugely useful. For Presence, this was further encouragement: evidence that we could vary the ‘casting’ and preparatory approach to the readings to the benefit and enjoyment of participants and the writer, without anyone feeling or being exploited. Mutual enjoyment AND utility, driven by a shared love of the dramatic phenomenon. What next? There followed a gap as we put together a sequence of further possibilities: new writing, international collaborations and challenging classics. By the middle of August (ok, quite a gap...) we were ready to ‘launch’, the aim, aside from continuing to vary the material, was to keep trying a slightly different approach each time. Session 2: Friday 21st August: Participating (from the top, above, line by line from left to right) Ami Sayers, Colin Ellwood, Sakuntala Ramanee, Jamie Newall, Susan Raasay, Valerie Gogan/Simon Usher, David Whitworth, Alex Wadham, Simon Furness, Stephen Cavanagh We have always wanted to tackle the rich text and dramaturgy of Early Modern drama, but the sight-reading spontaneity of our usual practice tends to hit a brick wall with the density of both text and plotting in your typical Elizabethan/Jacobean play. So the general call-out for this session (it was mid August…holiday season…would anyone be available?) was for one of the most knotty and dense texts and plots of all, John Webster’s 1612 tragedy The White Devil. Here was a challenge potentially yielding fantastic dividends if we could fine a way to unlock them, while at he same time preserving the groups characteristic reading spontaneity. The plan was to pre-cast from whoever answered the call-out, approaching others directly as necessary to fill any obvious gaps. Participants would then be informed in advance of their ‘casting’ and offered an hour’s prep/rehearsal by zoom in the couple of days prior, to tackle the language, talk about character or clarify plot and situation, whichever was felt most useful. This would then be supplemented on the day with brief synopses of each upcoming scene as we read, just to remind people of the core action in each. We got almost the perfect number of volunteers for all of the main roles, some shared, and decided that ‘White Devil’ herself Vittoria Corombona’s five 'marquee/tour de force' scenes should be shared between the five women participating. The brief ‘rehearsals’ seemed enjoyable, validating and clarifying, and allowed us to discover many useful and energising things, while acting to ‘release’ rather than to ‘impose’. And then on the day itself we gradually discovered this most supple, packed and theatrically powerful of plays. What struck me most about the reading was the energised and sure-footed commitment of all, and the finely calibrated series of psychological studies and carefully nuanced, charged relationships that slowly, measuredly emerged. Webster seems to have spent years writing the play and it (in a good way) showed. Central amongst the intricately unfolding strands was the story of the talented but impoverished Corombona family: the (eldest) daughter Vittoria; elder son Flamineo, and the youngest and least tainted of the siblings, Marcello - this latter the untainted apple of his widowed mother’s eye. All are thrust into a vortex of aristocratic desire, power and frustration embodied by the mercurial, immature 'subaltern' aristocrat Duke Brachiano, who in his desire for Vittoria lunges to escape what he perceives as the smothered affections of an older - and much more psychologically mature – wife, Isabella, and her controlling ‘Capo’ brother the Duke of Florence, backed up by the arid, cheeseparing misogyny of Cardinal Montecelso, soon Pope. Other beautifully and sparingly etched psychological portrayals are the menacing, banished Duke Lodovico - another junior noble beadily eyeing Brachiano as the close rival he is determined to destroy; the all-seeing, much-abused and strangely accepting Zanche the moor, Vittoria’s maid, and the plangent and ultimately tragic figure of the siblings’ mother Cornelia. Even what can seem on the page as incongruous, such as the latterly bizarre, almost absurdist, fish-out-of-water, voyeuristic behaviour of the Duke of Florence, in the reading/performsance acquired a sinister, odd, edgy, ambivalent psychological currency (is he in love with Vittoria or are his motives darker or more psychotic than that?) . What emerged was far from the genre-constrained blood-fest of reputation, but a supple, well-observed and deeply felt drama, hugely insightful in its psychology and in its class awareness. Overall the reading was measured, immensely committed, and also – as importantly – still charged with a sense of spontaneity, lifting and energising the limited prep we had managed to do. The general feeling afterwards that with this approach, a whole new and very exciting tranche of repertoire and a mode of exploring it is potentially opening up for Presence and for the group. Session 3: Mon 31st August: Participating (from the top, above, line by line from left to right) Zara Tomkinson, Colin Ellwood, Ami Sayers, Layla Jalaei, Susan Raasay, Hemi Yeroham, Adam Tyler, Anthony Ofoegbu, Alexis Diamond, Kevin McMonagle, Jack Paterson, Sakuntala Ramanee, Marie-Hélène Larose-Truchon Building on the discoveries of all the above, we then expanded to international horizons, in a co-endeavour with Canadian director Jack Paterson and his company BoucheWHACKED. Jack offered us a choice of three Quebecois texts in translation. Of these, for me, the clear standout was Midnight by Marie-Hélène Larose-Truchon in translation by Alexis Diamond. An extraordinary rich, bold, theatrical and beautifully shaped dystopian tale of three generations of women – Grandma, Midnight and Girl – trying to hold on to memories, family, culture, lore and language in the stark corrosive searchlight of a decidedly male and bleakly utilitarian regime that denies all aspects of the past - including old age - as well as subjugating all aspects of the feminine. And that polices its sleazy, misogynist regimen by means of a children’s army of brainwashed adolescent ‘angel-knights’. One of the latter seems tentatively to fall for Girl, but is this simply a device for getting access to Grandma in order to euthanize her, as the ‘law’ demands for all elders? Meanwhile Girl is slowly introduced to the family mythology of her birth and of her mother's childhood; then to the ‘coven’ of the family's cross-generational matriarchy and to their illicit ‘word and memory hoard’ of which the ultimate custodian is Grandma. Hovering in the background is Girl’s father, The Electrician - the ex-lover of the steely but wayward (and electricity- and attention-addicted) Midnight - a fixer and amateur taxidermist (death AND the past, there…) who still holds a candle (literally) for the mother of his daughter. This is a tale that comments on society in its current present-tense, utilitarian fixation, but also offers a myth of growing up and growing out, of accepting death and understanding the transitory, evanescent preciousness of memory and experience. An extraordinary, lyrical, linguistically-soaring, theatrically sure-footed, deeply and richly imaginative and original play, miraculously translated by Alexis Diamond . For this we cast specifically from within the reading group, double casting pretty much each role (except one), and with the actors either alternating scene by scene in a role or splitting the role into consecutive halves, whichever seemed more appropriate. And again, as with White Devil, over the preceding couple of days we had brief solo sessions on zoom with most of the performers. The results, the reading itself, seemed to soar. Playwright Marie-Hélène and translator Alexis professed themselves 'over the moon' with the results. The play was a joy to engage with, to explore and to read. Would that dramatic writing of this quality, deftness and imaginative heft were more available in the UK. MIDNIGHT (MINUIT) photo: Javier Allegue Barros @ unsplash.com On 31st August members of the Presence reading group had live-read via zoom a translation by Alexis Diamond of Quebecois playwright Marie-Hélène Larose-Truchon's play MIDNIGHT, joined for the event by Canadian director Jack Paterson, translator Alexis Diamond and possibly the playwright herself. In an act of resistance against a despotic government that hunts down seniors and sucks their memories dry, the irrepressible Midnight keeps her mother in hiding, to protect her and her daughter and their secret world. They swap knowing smiles and lost words while braving a lack of food and light, driven mad with love, anger, fear. This homage to a fading civilization stirs up snow and subversion, ancestral culture and instinct: craved, warped, misused, a past re-animated and electrified, just like new. This translation was commissioned by Talisman Theatre, artistic director Lyne Paquette. Translation dramaturgy was provided by Linda Gaboriau. Dramaturgical support for the translation was provided by Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal (PWM), artistic and executive director Emma Tibaldo. Cast includes: Layla Jalaei Kevin McMonagle Anthony Ofoegbu Susan Raasay Sakuntala Ramanee Ami Sayers Zara Tomkinson Adam Tyler Hemi Yeroham Marie-Hélène Larose-Truchon (Playwright) A year after graduating from the National Theatre School of Canada’s francophone playwriting program, Marie Hélène Larose Truchon won the Le théâtre pour les jeunes publics et la relève playwriting award for her play Reviens!, and received special mentions at the Prix Gratien-Gélinas for Minuit (2013) and Un biseau m’attend (2015). The latter two plays were given staged readings (in 2014 and 2015 respectively) at the Centre de auteurs dramatique’s Dramaturgies en dialogue festival in Montreal. A coproduction of Minuit by the Théâtre Double Signe and the Petit Théâtre de Sherbrooke was presented in Sherbrooke (2017) and Montreal (2018). Marie Hélène teaches playwriting at the National Theatre School of Canada French language program and is working on several writing projects for all-ages audiences. Her play Crème-Glacée was produced by Théâtre La Seizième (Vanco Alexis Diamond (Translator) Alexis is an anglophone theatre artist, opera and musical librettist, translator and theatre curator working on both sides of Montréal’s linguistic divide. Her award-winning plays, operas and translations have been presented across Canada, in the U.S. and in Europe. She also collaborates internationally with artists on performance-installations involving text, movement and sound. In 2018, Alexis began a multiyear collaboration with professor Erin Hurley (McGill University) and Emma Tibaldo (Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal) researching the history of English-language theatre in Québec. In May 2019, Alexis Diamond served as co-artistic director of the famed Festival Jamais Lu, where she presented the mostly French-language Faux-amis with co-author Hubert Lemire, supported by CALQ. Her theatre translations are also in wide circulation: upcoming tours include The Problem with Pink by Érika Tremblay-Roy, published by Lansman (Le Petit Théâtre de Sherbrooke), and Pascal Brullemans’ The Nonexistant (DynamO Théâtre). Three translations were presented in the 2018-19 season (for Geordie Productions 2Play-Tour, Talisman Theatre and Le Petit Théâtre de Sherbrooke). Her translation of Pascal Brullemans’ plays for young audiences, Amaryllis and Little Witch, was just published by Playwrights Canada Press. Currently the Quebec Caucus representative for the Playwrights Guild of Canada, she is co-founder of Composite Theatre Co. and a long-standing member of Playwrights’ Workshop Montréal. She has a B.A. in Creative Writing (Concordia University) and an M.A. in English Studies (Université de Montréal). About Francophone Canadian Theatre Quebecois and francophone Canadian playwrighting is on forefront of international playwriting - their work is translated and presented all over the world. Like much European writing, Quebecois texts are written to engage the artists involved as well as their audience. Textual presentation does not define production but engages in theatrical imagination and expression, embracing metaphor as much as much as English Language writing often embraces the well-made play. In short, the text is often only the beginning of the theatrical conversation. It’s particularly hard to describe the unique “Langue D’Auteur” created by Francophone Canadian artists as there’s nothing quite like it in Western English Language theatre. Imagine Shakespeare, Moliere, Sarah Kane and Martin Crimp smashed together. It was developed in part to allow Quebecois artists to write for French language touring without sacrificing their own cultural and linguistic identity, and in part as a textual equivalent to the remarkable physical theatre and literature of the culture. It is a textual place where there are no rules or the rules are meant to be smashed. The poetic or expressionistic are side by side with gritty realism and the mundane often becomes the fantastical. BoucheWHACKED! Theatre Collective (Vancouver, Canada BoucheWHACKED! Theatre Collective is a Vancouver based collective made up of working theatre professionals dedicated to the development, production and presentation of multi language works, cross disciplinary practices and works in translation. With a specific focus on cross pollination between International, Canadian Francophone and Anglophone artists, BoucheWHACKED! aims to bring together the thriving talent that exists in communities separated by distance, language, and culture. www.bouchewhacked.co Jack Paterson Launching from Vancouver, Jack is an award winning director, divisor, dramaturge, translator, actor and creative producer whose study and practice has taken him across Canada, the United Kingdom and around the world. His work has ranged from contemporary devising, cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary projects to main stage and classical theatre in contemporary form. Recent projects include collaborating on the Global Hive Labs. international devised creations Atlantide (Teatro Trieste 34, Italy) and Medusa (Steppenwolf Theatre, USA & The Pleasance and Cockpit Theatres UK), leading the cross-cultural devised creation Balinese Folk Tales (SENI Indonesian Institute for the Arts Denpasar), dramaturgy for the disability arts project Cowboy Tempest by Niall McNeil (Vancouver). Last fall, he spent three months with the German innovation incubator flausen+ (theatre wrede+, Germany). www.jackpatersontheatre.com SUMMER SUSTAINED. 14TH OF SEPTEMBER. Session 4: Monday 14th September: Participating (from the top, above, line by line from left to right) Jennifer Woodward, Colin Ellwood, Jamie Newall, Carla Grauls, David Whitworth, Rachel Bavidge, Alex Wadham, Charlotte Pyke, Kevin McMonagle And finally - more SUMMER SUSTAINED than SUMMER SEASON - back to the UK to read Carla Graul’s Nick Darke Award winning (but not yet performed) Made For Him, with the writer attending. Another sharply dystopian and disturbing take on the future, or maybe just an intensified look at the present, this time focusing on misogyny and A.I., while also exploring the nature and definition of ‘reality’ – perfection or with flaws… A future-world sex-doll is given innovative emotional circuitry, and in her/its development phase almost has a secret affair with a ‘real’ woman - the cleaner in the laborotory in whicnh she is being developed, In parallel she is being made to satisfy the sexual demands of her human developer. These scenes are cleverly interspersed with encounters from her later life with her new purchaser. In these latter, the combination of her new emotional circuitry and perhaps the memory of her bond with the cleaner make her unsatisfied with what her new ‘owner’ offers and expects, and she yearns for much more than the emotionally stunted stale male ‘consumer’ can offer. Some very dry, dark humour here on male behaviour and status anxiety add to the unsettling cleverness of the double time-sequence (we don’t know that the alternate scenes are in different time phases and that the central character in each is the same ‘doll’ until quite late) in a drama that anatomises human desire (specifically male desire) as it manifests in an acquisitive consumerist society. The emotional circuitry of ‘Beta Iris’ is too much for purchaser ‘George’ and indeed for the android herself, so she makes her escape/is decommissioned, while he goes back to a less advanced model with fewer human characteristics, so in George’s terms, fewer flaws and more 'real'. A wonderfully ambivalent ending – ambiguously placed in time – where she seems to feel a sense of agency/freedom as a collector of almost extinct moths… The tone of the whole play is deliciously deadpan and deeply disconcerting. For this session we put out a general call, knowing that we needed more-or-less equal numbers of male/female participants (and that’s what we got); then in the standard Presence way, we spontaneously shifted roles around scene by scene, so everyone got (I think) a go at pretty much all the main characters and pretty equal opportunities overall. original photo by: I-Am Nah @ unsplashed.com We are pleased to announce our next reading exploration: a new play by Carla Grauls. On the 14th of September members of the Presence reading group will live-read via zoom Made For Him, which has not been previously read or performed in public. We will be joined for the event by the author. A full account on our reading group blog soon. Participants/Readers to include: Rachel Bavidge, Kevin McMonagle, Jamie Newall, Charlotte Pyke, Susan Raasay, Zara Tomkinson, Alex Wadham, David Whitworth, Jennifer Woodward

Carla Grauls Carla is an award winning writer based in London. Her play Me Myself I was performed at the Vaults Festival this year. In 2018, she was selected for Audible's Emerging Playwrights Fund and wrote Life Ever After. In 2017, she was shortlisted for the Yale Drama Series Award for her play Natives. In 2016, she was selected to write a short play for Promised Lands, a playwriting festival based in Milan. In 2014, her play Occupied was produced at Theatre503. In 2013, she won the Nick Darke Award. |

INDEX of dates:

INDEX of playwrights and plays:

INDEX of contributors:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed