|

Friday 11th December

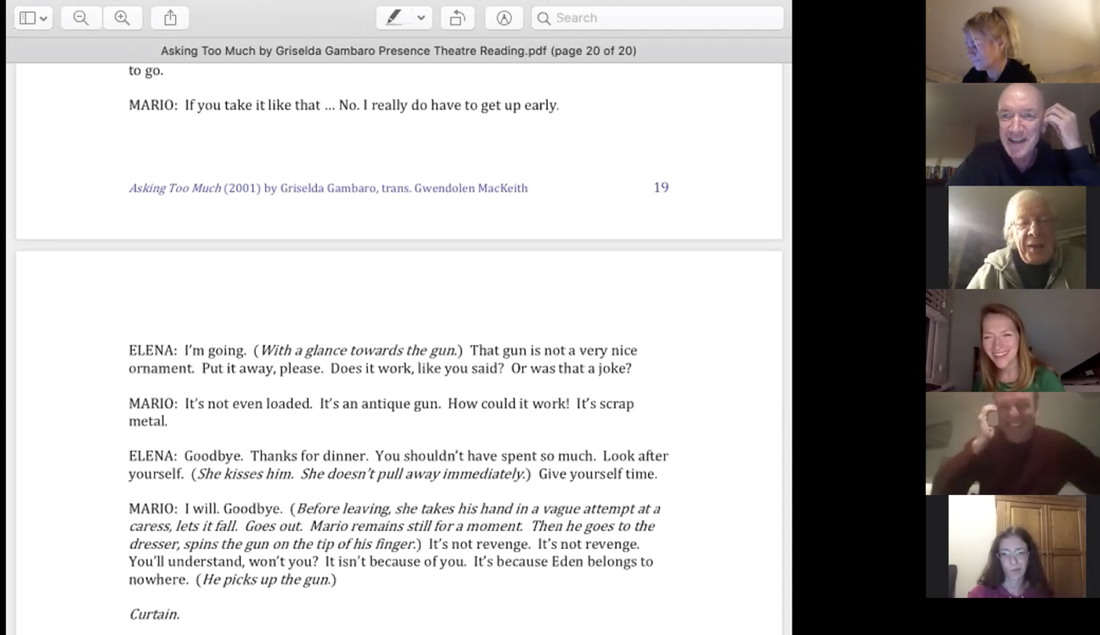

Present (Row by row from left to right): Gwen MacKeith; Colin Ellwood; JAmie Newall; Susan Raasay; Emmanuela Lia; Adam Tyler; Simon Usher; Kevin McMonagle; Julia Winwood; David Whitworth; John Chancer; (Valerie Gogan)

A real pleasure to be reading Gwen MacKeith’s new ‘in-development’ but already very accomplished translation of eminent Argentinian playwright Griselda Gambaro’s extraordinary 2012 spin on Ibsen’s A Dolls’ House. In Dear Ibsen, I am Nora, Gambaro imagines Nora conjuring the playwright himself into her drawing room, for guidance and also to help with her growing sense of existential unease. A sharply-compressed version of the original Doll’s House action ensues, with Ibsen pretty constantly and sometimes unsettlingly in attendance advising his principal character (and occasionally the others) while also attempting to construct and manage the play in real time like a frazzled Victorian Mike Leigh operating against the clock. This clever conceit occasions both a meditation on the messy process of writing plays in general, and a probing of the politics, possibilities and prevarications of Ibsen’s classic in particular, as playwright and central character engage in a sometimes fractious dramaturgical collaboration. Gambaro also mines the socially-comedic potential of Ibsen's incongruous half-presence as an awkward middle-aged celebrity, resented and sometimes even rebuffed by his own characters. The great man is in fact presented here as a kind of evolved version of Nora’s husband Torvald who, Gambaro's conceit implies, is himself a dramatist manqué, attempting to impose an even more reductive dramatic narrative on his mercurial wife. In fact Ibsen is shown as having a strong vested interest in Torvald’s efforts, since forcing Nora into implausible genuine dolls-house infantalism at the beginning of the action (when in fact she is already very much experienced and is deftly managing a difficult reality) serves to optimise the character’s subsequently dramatic journey. In some ways Nora is here more astute than her author, sometimes lashing out in exasperation at the weaknesses of the latter’s dramatic carpentry as the play unfolds. Nora even points out the absurdity of there being so many entrances and exits in what is supposedly a private drawing room. Are these 'weaknesses' in general functions of Ibsen as an individual, or of his historical and cultural context, or simply the necessary elisions and compromises of playwriting itself, the collateral damage involved in wresting dramatic impact and meaning out of reality’s flow? Gambaro expertly keeps all these options in play. At the same time she justly honours Ibsen’s genius and his genuinely revolutionary qualities: this is very much one great dramatist hailing an honoured predecessor. There are many telling, witty and insightful moments and tropes: Ibsen shown as being ‘in process ‘(‘I don’t know yet’); his having different relationship with different characters, for example being slightly scared of Torvald, and Dr Ranke bearing a grudge against him for his dramatically-convenient fatal affliction. It is Nora's impoverished friend Christina who is depicted here as taking the initiative on Nora’s ultimate admission of 'guilt', advocating the value of pre-emptive disclosure directly against Ibsen's wishes. Gambaro also underlines Ibsen’s awareness of the financial and class constrictions in the situation as well as the gender ones. There is a telling moment when three middle-aged men – Torvald, Ranke AND Ibsen - go off to letch at Nora practising the tarantella. Gambaro at times daringly sharpens Ibsen’s dramaturgy, for example intensifying the Cristina/Nora contrast, with Cristina shown as having the courage to accept a family, just as Nora finds the the courage to reject hers. A key and hugely effective moment of silence between Christina and the blackmailing Krogstadt beautifully parallels the subsequent silence between Torvald and Nora (the former employing an emotional blackmail). The main focus throughout though is on Nora. Gambaro’s Ibsen guides her, advises her, corrects her and puts obstacles in her way as she explores dramatic solutions to her problems. In turn she questions Ibsen’s intentions for her: will she be a heroine? Commit suicide? In the end Gambaro’s Ibsen does not ‘abandon’ Nora. This is strangely moving and perhaps here there are shades of Flaubert’s ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi’. When Torvald, the apparent danger of his 'disgrace' over, offers to forgive Nora as she had hoped/fantasised, Ibsen seems conflicted. Will he settle for this more conventional ‘miraculous’ ending? In the end the playwright is shown as being redeemed by his character's unruly courage, and so it is not just Torvald’s doll’s house latter escapes, but also Ibsen’s. In the process she rejects his subsequent assertion that he created her and so should control her: She exists, she asserts, already, and with her own potential. And that of course, is partly (only) also a covert tribute to Ibsen’s greatness. In the end, after a (third great) pause/silence, Ibsen wishes her valedictory luck. And so Gambaro shows them both as pathfinders, revolutionaries. We concluded the session with a second, earlier MacKeith Gambaro translation, the beautifully ambiguous, sometimes Pinter-esque short two hander Asking too Much, astutely exploring emotional blackmail and tacit emotional support in a relationship that may or may not be ex-partners enacting a kind of covert role-play. A great coda that perfectly occasioned a kind of balanced and equal ‘round’ of partnerships for all attending

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

INDEX of dates:

INDEX of playwrights and plays:

INDEX of contributors:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed