|

February 12th. Present: Robert Lightfoot; David Whitworth; Susan Raasay; Valerie Gogan; Simon Usher; Ami Sayers; John Chancer; Paul Hamilton; Juliet Prague; Layla Jalaei

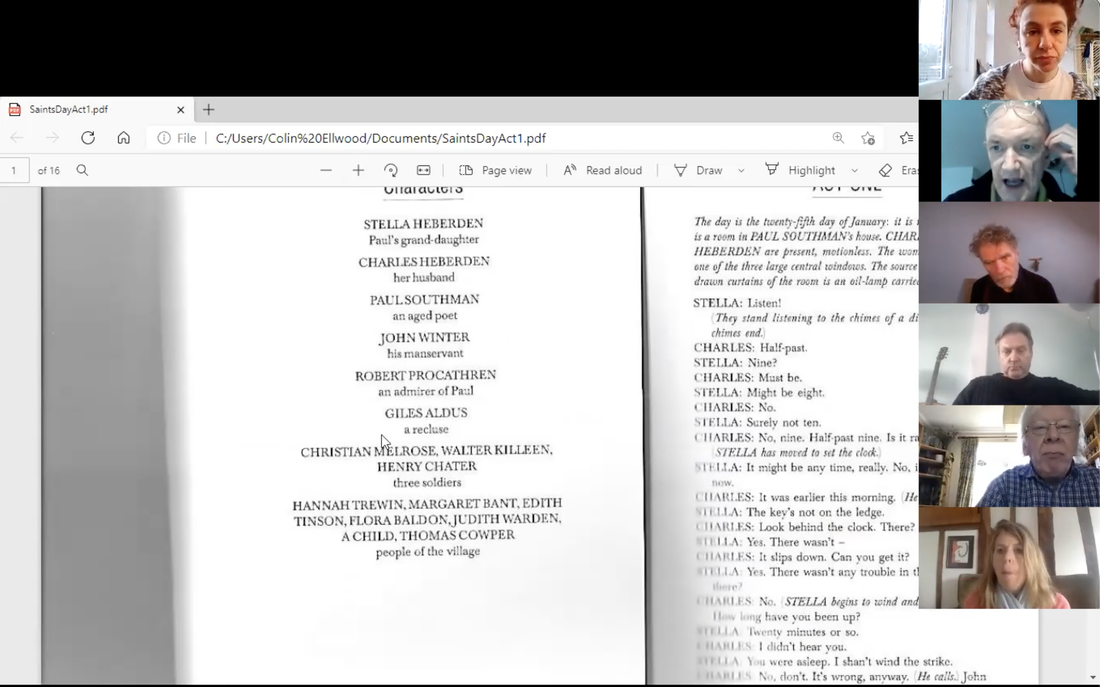

Back across the Atlantic for John Whiting's mordant 1950 Saint's Day. Agatha Christie's The Unexpected Guest meets T.S Eliot's The Family Reunion via Golding’s Lord of the Flies. A rackety and impoverished country house of resigned, retracted artists under virtual siege from a hostile village and runaway psychopathic soldiers. Subsequently a minor poet-critic runs amok having been bullied and taunted into inadvertently and randomly shooting someone through a door. In the end, the three (deserter) foot-soldiers-of-the-apocalypse, partly corralled by the now feral poet-critic, string the resident artists up on two dead Golgotha-evoking trees. Overall a brilliant excavation of the underside of Festival of Britain optimism and a foreshadowing of Pinter, David Rudkin and Lindsey Anderson. And great fun to read this psychotic, symbolist-inflected twist on the country-house drama. So…an isolated country house, inhabited by reclusive, penniless, rejected, once feted, artists overseen by an apparently senile patriarch. Then the outside world comes calling, firstly via the young critic-poet come to chaperone the patriarch to a supposedly redemptive literary dinner in London in honour of his birthday, and then ultimately in the form of three psychopathic deserting soldiers. The importunate niece of the writer-patriarch is the one who takes the random bullet; the poet-critic is bullied into a kind of savagery; and the patriarch reveals he is not quite so senile after all when given purpose in a class-war. The two original rejected artists – the old writer and a young painter who has previously retreated from London in terror at the critical world - are in the end accorded the Calvary treatment. Meanwhile the very antagonistic local village gets torched when the local vicar burns all his precious religious books in his fireplace and things get out of control. Throughout, the atmosphere is charged, strange, artificial and highly symbolic. The play reads amazingly, in a hermetically sealed sort of way - almost a guilty pleasure, if a little over-loquacious at times. Hints of Lyndsay Anderson’s If in the casual bullying meted out by the upper-classes on their perceived inferiors, and – linked to that – of early Pinter. Lots of strange names that nonetheless seem so right such as ‘Procathren’ and the inscrutable, much put-upon man-servant who is always accorded his full name when summoned: ‘John Winter’. This was Whiting’s first play. Is it in earnest or a confection, an exercise? The feel of it is more like one of those slightly psychedelic films of the 1960s. It certainly doesn’t take place in what we might take for recogniseable reality and it achieves its effect by vivid assertion rather than bottom-line plausibility. But it always seems to know where it is going and unfolds in accord with a deeply satisfying internal logic that is surprising but also, on arrival, inevitable-seeming. Yes, a confection, a brutalist dream play, but the difference between artificial confections and ‘serious’ and earnest state-of-the nation realism seems to matter less now ….just think of the dramatic worlds of Philip Ridley. This has something of the same kind of sealed, simulacrum-world quality. And it absolutely stays with you, as a siren song conjuring a flavour of right-wing conspiracy, a class-conflicted world in which affectless roundheads are presented as taking over… an enlightenment world gone rotten. In doing so it seems to predict the dark conspiracy theories and rumoured coup plots characteristic of the UK in the early seventies…. On the basis of this could you perhaps call Whiting the great lost playwright of the right? His view of human nature is dark to say the least, unalloyed, and because his action and world are so ‘unreal’ yet so well internally supported, he has the knack of creating a sense of the numinous, of offering a stark myth, an inscrutable parable relished with an underlying sense of latent violence. He died in 1963 at the age of 45. This play absolutely touches a nerve still, and here elicited some rich and wonderfully characterful readings here. Whiting’s slightly later Marching Song would be his next play to look at I think

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

INDEX of dates:

INDEX of playwrights and plays:

INDEX of contributors:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed