|

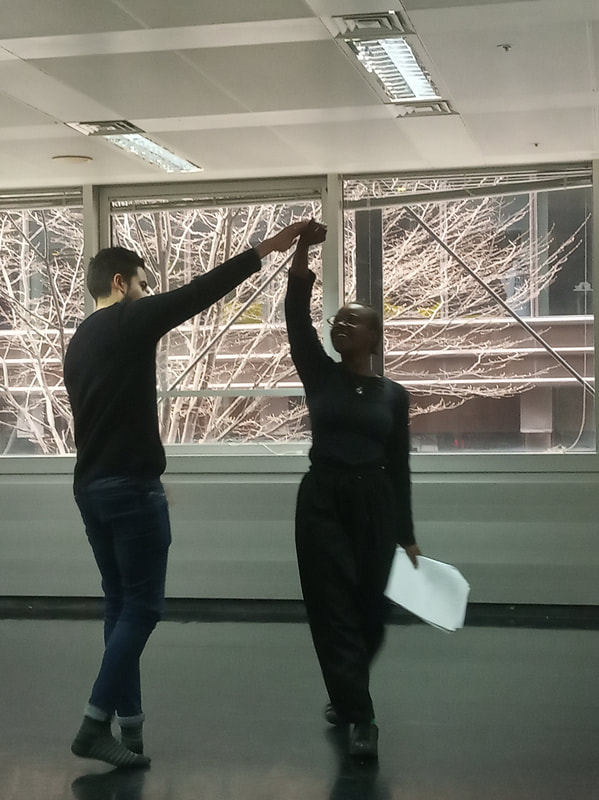

Photos: Anna Mors Text: Colin Ellwood The Presence Actors’ Monthly Play Reading Group Feb 28th….and beyond. Two great days of script exploration at Presence, this time in partnership with our good friends at Unge Viken Theater in Lillestrom, Norway. On Friday our regular play reading group on at the IES centre in Holborn, welcoming playwright Regine Rossnes and Unge Viken’s dramaturg Oystein Brager to hear Regine’s play Exposed. Then on Saturday heading to Theatre Delicatessen’s brilliant re-purposed space in the City of London for a full day’s exploratory work on the script with performance students from Rose Bruford College Friday, The Presence Actors’ Play Reading Group Friday’s session began with an almost-full house of reading group regulars, and with Oystein and Regine from Unge Viken still hurtling along the Piccadilly Line, their early morning flight from Olso having been slightly delayed. While waiting for them we started with Gregory Motton’s 2017 A Worthless Man. It’s a challenging, complex script, and as such warrants close and detailed consideration: The following is not that, but rather preliminary reflections drawn from hearing the play read aloud on Friday. The play is a series of interweaved stream-of-consciousness monologues: Two families, one working class, one kind-of bohemian bourgeois (both denominations not quite adequate in the plays mapping of a polarising social landscape). Each family consists of a mother, father and just-grown-up daughter, and all are notionally in bed alone in the moments before sleep, remembering their day and reflecting on their relationships with each other and with the wider world. What begins as class satire, ends in existential despair (or at the most optimistic, as a bleak call to arms). Extraordinarily vivid metaphors bubble into the monologues ultimately threatening to un-seam the fiction, leading us progressively from the astute revelation and pointing of attitudinal absurdity into richer, darker territory. It’s as if the characters, on their way to sleep, become latterly themselves dreamt, and by an imagined consciousness in melt-down, or one achieving a very primary sort of creative clarity. Hieronimo may or may not be mad again. The father of the more ‘upscale’ family is a marketing executive-cum-college lecturer who deploys management-speak conceits with an impressive but sinister grace. Progressively he is revealed as a demented identity-fascist, striving for a book-burning Year Zero of continual revolution, all history, and all material and biological reality, nullified in the cause of extreme libertarian self-reinvention. All, that is, apart from the ethnic, gender and cultural identities that form the cornerstones of current identity politics, to which he offers a pious obeisance. The contradictions here are clearly part of the satirical point. The mother craves ‘experience’ at any cost (the cost being always on other people’s tabs) up to and including cannibalism; the daughter amuses herself by inventing bizarre self-identities while crassly overriding the obvious and painful material and economic conditions endured by those less fortunate than herself. In fact the whole family in their enormous sense of entitlement are utterly oblivious to the material and cultural resources that underpin their narcissistic gravity-free posturing. If the play’s posh family strive for continual cultural revolution, the other, or at least its father figure (an ex-miner turned septic tank engineer), dream ineffectually of real political and socio-economic insurrection. For them, the despair is borderline existential and Motton’s portrayal is fundamentally empathetic. The play’s starkest and bleakest metaphors surely belong to this family’s daughter Frizzy, who keens at the meaninglessness of words as an alienating tsunami of bad-faith noise. She likens herself at one point to a self-ravishing nun (not sure that one quiet works, but it somehow does in the play’s almost psychedelic later stages). The insidious and alienating bad faith of language is a key focus throughout, as the satire gradually straitens and dissolves into spectral bleakness, before finally shuddering to a conclusion with a gesture that can only be termed, oxymoronically, sublime bathos. On Friday the reading began with a savouring of the social satire and absurdity before slowly retracting into something less certain (while maintaining a commendable richness of characterisation and relish of language) as we realised we weren’t in Kansas any more. Surely this is the exact trajectory that any production should seek to induce in the audience, as the sarky anger and subversive mischief of the opening become cut with pain and finally bitter despair. At the end, words kind of failed us (as the play surely prescribes….). Motton might be both Caryl Churchill’s lost dark twin and also possibly her worst nightmare. Chastening. As we entered the final pages of A Worthless Man, and with immaculate timing, the Norwegians arrived. Regine Rossnes is a slam poet, and her play Exposed, newly translated with scary slam-aplomb by Neil Howard, is set in a Norwegian high school where new student and free spirit Eili’s sexual indiscretion with her recently-ex boyfriend’s (possibly ‘supposed’ boyfriend’s ) best friend gets uploaded and shared around Snapchat, with devastating effect. If, for Motton, words are simply lies, for Rossnes, they are ultimately valid instruments of expression and potential moral good, and her play accordingly offered a contrast to the near-despair of A Worthless Man. Exposed is a play where moral choices are difficult but conditionally valid, and positive trajectories at least not out of the question. Short stark duologues and trios alternate with slam-poetic interior monologues, embodying a world of intense group loyalties under pressure from new adolescent feelings, experiences and temptations. The ending of the play offers a positive way forward for the characters that is (deliberately) troubled and troubling, but made possible at all through a central and defining act of bravery and solidarity on the part of the two main ‘wronged’ characters. Calibrating that marginally-positive ambivalence, while also mapping the intense shifting emotions and impulses (in all the characters not just the easier-to-like protagonists) that lie beneath the play’s explicit teenage censoriousness, is surely the play’s central endeavour. Our reading yielded some fascinating discoveries. Of course this is a spontaneous reading, and expecting full-on emotional availability in such circumstances is of course mad, but perhaps there is also something else going on here. No-one in the group is in the right age range of course (sixteen to eighteen), hence perhaps a slight hesitation to inhabit and internalise the required teenage argot and emotional world. Our culture’s centre of gravity now is arguably the teenager, so the attempt of anyone over the age of twenty to fully commit to a teenage structure of feeling or (related) means of expression maybe feel like an act of aspirational delusion. On the other hand it might be that the teenage ‘identity’ is even more fraught with posturing, self delusion and protective cliche than the ‘adult’ one, and this triggers the reluctance of more world-wise and absurdity-wary adults to engage other than ironically. Or maybe teenaged earnestness – or all earnestness (and teenaged earnestness is surely the purest kind…) - is tricky, in our cynical and wary culture. Anyway, fascinating. What the reading also reveals, I think, is that beneath the play’s teenaged hedging and posturing (and the play seems to delicately map many such manoeuvrings) lies a well of unconditional, categorical, intense and authentic feelings. It is in fact this ‘charged’ reservoir or root that infuses the script with its poetry (one key strain of poetry surely being by definition instances of simple language and gesture containing or restraining complex, rich, intense ambivalent feeling) and such is evidence in Exposed, as much in the short, terse dialogue exchanges as it its explicitly ‘poetic’ inner monologues. Rendering the former ‘conversational’ (as seemed understandably sometimes the intuitive tactic in the reading) doesn’t quite seem to work. For one thing it disguises the various genuinely (and beautifully defined in the script) failed ‘conversational’ gambits in each exchange that are eviscerated in almost every case by the characters’ emergent deep feeling. For another, it simply dislocates the link to that underlying ‘root’ of feeling that sharpens the exchanges. If the play’s poetic language of the ‘slam’ monologues is about emotional expression, its poetry of the dialogues is about the containment of emotion. Thinking of this ‘teen-spirit’ – expressed AND contained - I kept thinking of the way actors tap into and inhabit the (to us as contemporary adults) in some ways equally ‘alien’ unconditional and emotionally-absolutist worlds of Lorca’s plays or of the Spanish Golden Age writers. Such clarifications and hunches are of course made possible through the wonderful glittering, ‘tessellating’, multi-faceted and multi-voiced instrument that is the Presence play reading group… After the reading, a wonderfully energised discussion ensues around the issues arising in the play, such as the ethics of image-appropriation in relation to the demands of ‘old fashioned’ sexual morality; and the crudeness of the tools currently used by adults to manage this kind of teenage behaviour, tools such as the legal system that inappropriately scar both victim and perpetrator in non-proportionate ways. Whatever else the virtues of the play, it absolutely – and necessarily - touches a very sensitive and current cultural nerve. After a late (and short) lunch we reconvene to read Lucy Kirkwood’s 2012 Royal Court NSWF, in which a ‘lads mag’ publishes a photo of the breasts of a fourteen-year-old girl without checking her age, and her father subsequently arrives at the magazine’s offices. As with Exposed, we have here the exploitation without consent of an underage sexual image, but the lens is very different. Instead of starkness and poetry we have an extremely focused, sharp and very telling satire on hypocrisy and venality. Not unlike the Motton, but with a more defined strategy of attack and without the incipient existential despair. Here the hypocrisies and MOs of the (2012) popular media are used as a way of exposing a society built entirely around the commodification of everything for financial gain: innocence, desire, family relations, the body, intimacy. The third act is set in the offices of a new women’s magazine where similar strategies are deployed: a plague then on both your gender identities… the issues are therefore ultimately posited as being of class and culture rather than gender-related. The play is a riotous read, and with some very deft and clever performances in evidence as the roles circulate round the group. After that, to the pub. Saturday, R&D Workshop on Exposed at Theatre Deli. On photos: Rose Bruford ETA students: Amelie Eberle (assistant director), cast - George Attwill, Rebeka Dio, Tatenda Matsvai, Bethan Barke, RB Acting student Alamo Perez, dramaturg Øystein Ulsberg Brager (Unge Viken Theatre), Theatre Delicatessen (fantastic rehearsal/dance studio!) and finally Regine Folkman Rossnes, and director Colin Ellwood. If Friday was a chance to hear and explore Regine’s play with the great combination of seasoned professionals and deliberately un-prepped spontaneity, Saturday was an opportunity to work on the text in a more forensic way and on the rehearsal room floor. We meet at 10 am on a very wet day at the fantastic Theatre Deli facility near Liverpool St Station. It’s a beautiful, thoughtful transformation of a standard commercial office space, achieved with huge attention to detail. We are in the ‘dance studio’ for the day and it’s perfect. ‘We’ are myself , Anna Mors, associate producer and director from Presence, Oystein Brager, dramaturg from Unge Viken, Regine Rosness, poet and playwright of Exposed, and a group of Rose Bruford European Theatre Arts and (one) Acting programme student: George Atwill, Bethan Barke, Rebeka Dio, Amelie Ebert (in the position of assistant director), Tatenda Matsvai, and from Bruford Acting, Alamo Perez. The plan had been to rotate casting of the play’s five characters scene-by-scene, but on the way in, and thinking about who we have, a casting suggests itself and seems to ‘chime’, so I decide to go with that subject to possible later experimentation. The intended strategy in other aspects is also still fluid: we can work comparatively quickly through the play (it’s probably about forty minutes long in performance) and then end the day with a rough-cut ‘run’, or we can be more selective and work in detail on particular scenes. A lot will depend on what is most useful to Regine. The initial feeling in the room is excellent: open, relaxed and playful yet concentrated. After around forty minutes of warm-up and physical and emotional limbering we ease into working through the play. The first short scene involves Rebeka as Helen the ‘leader’ of the small group of girls newly arrived in the upper school, and Bethan as her friend the ever-triangulating Miriam. Questions tumble out, and slowly a rich, specific, complex and internally-consistent dramatic world is constructed, or rather ‘uncovered’. In the best dramatic writing of course, the ‘constructed’ and the ‘uncovered’ are functionally indistinguishable. Even more tellingly, the text begins to confirm itself as terse, stark and sparely transactional; a high wire act of character decision-making in extremis. The actors are initially maybe a little nervous and ‘demonstrative’, but fairly quickly they release and settle into the grounded-ness of the physical and emotional space opened out by the text. Character begins to emerge through action and decision; complexity and richness is realised through simplicity of action. The questioning and exploring of the silences and ‘undefined’ aspects of the text slowly leads to clarity, revelation and insight. You can almost hear each ‘docking’, each ‘click’ and the consequent small relaxations, rooting and expansion of individual performances. Gradually we seem to tap into the ‘root’, as the two characters subtly attempt to manipulate each other in their relation to Eili. There is no slack in this scene, everything is beautifully ‘loaded’ and balanced. The characters negotiate excruciatingly balanced decisions in their implicit game of brinkmanship. We move on. The next scene is the first ‘poetic’ monologue: Tatenda as Eili recounting her experience of the party where it all went wrong. As an experiential exercise (and maybe also a potential basis for staging ideas) a fairly spontaneous choreography emerges involving the whole group: part enactment, part distillation of the events Eili recounts, as she recounts them. A broader idea has been to have scenes emerge out of the ensemble embodying together the tight, tribal world of adolescent peer groups. This looks like it has possibilities, and we quickly get a rough cut, making use of some recorded music that Tatenda has brought and that coordinates scarily well with the action. The final scene of the morning is between Eili’s erstwhile ‘boyfriend’ Andre (George) and his best friend Benjamin (Alamo) who subsequently ‘got off’ with Eili at the party. It reveals a primal, hurt quality involving a dog-like growling and a guarded circling. Amends are rather haplessly attempted and suddenly the scene opens out onto another dimension: consideration of Eili’s perspective, she now having been completely ostracised from the group. This beautifully complicates the world-view of the boys and foreshadows the moral thrust the play will ultimately pursue.. A lunchtime conference confirms that the best use of the afternoon session is to choose some scenes for continuing detailed work. We decide on three, each no more than two pages long. They all in the event confirm what was becoming so apparent in the morning: Each one contributes to a complex and rich model of the characters, their world and the motivation for the choices they make. Any sense that the play is judging the characters’ natures rather than their action, dissipates. Everyone is to be or have been behaving badly out of need rather than desire, out of adolescent desperation rather than Machiavellian relish. The behavioural and emotional root of the play proves rich, multiple and complex, and its multiple, contradictory impulses are shaped and distilled to simple, fluid gesture. Staged, physical poetry. Like all effective dramas, Regine’s is about dangerous and delicate transitions on multiple levels, in this case between friendship groups and new sexual and emotional attachments; also between different cultural and generational groupings and between an ethical system centred around the expectation of sexual continence and one in which control of privacy and images in the digital age is paramount (socially and culturally we are clearly moving towards the latter). It features a group of people evaluating and making choices at a vertiginous ‘layering’ of levels: who slept with whom? Who filmed what? who distributed what film on social media,? Who spread rumours about the motivation and circumstances of any and all of these acts? How were these acts at all levels related as parts of a malign plan or simply random series of accidents? What is the relative moral weight of any of these act? Being a teenager now is complicated. At the end of the day we have a sense of the trajectories of five very clearly defined individuals, each melded and formed in relation to each other, and all making what feel to them like the most important decisions of their lives, and in at least one central – and very brave - instance, that is indeed possibly the case. A final discussion: in one of last scenes we look at, the character of Helen approaches the ex-boyfriend Andre and suggests that Eili had been cheating on him ‘all summer’. This is new in the play. Helen’s motives for saying this are questionable. Do we believe her? Is it true? If so, such is the thrust of the work on the play so far, it simply serves to make both Eili and Helen more richly complicated, more ‘human’ and less easy to judge. I turn to Regine. “What do you think?’ is her characteristic response. But we think, I think, what she already knows: The complexity and richness of the play warrants that choice, and on further reflection we see that this has clearly been embedded in the play by Regine all along (hence for example Helen and Miriam’s till-now slightly mystifying references in earlier scenes to Eili’s being ‘two-faced’). We discuss how a slight change to the text might aid this understanding – but that I’m pleased to say is up to Regine, not us. A final thank you to Oystein and Regine and of course to our Bruford performers, whose work showed the way to clear and committed characterisations: Rebeka’s high-strung, nervy, quite needy Helen; Bethan’s earnest, careful and conflicted Miriam; Tatenda’s impulsive and joyous Eili; Alamo’s rueful but determined Benjamin, and George’s canny, emotionally bruised Andre. It has been a great and releasing day, and in a month’s time we do it all again with a second play and writer, thanks to Unge Viken.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

INDEX of dates:

INDEX of blog posts: INDEX of contributors:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed