|

Emperor Fukushima at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe was the conclusion to Presence's Festival Season in 2016. For actor Tom Freeman it was a returning. Here he writes of these homecomings, legacy and the power of stories and unbridled energy. In many ways, participating in Presence Theatre’s performance of Emperor Fukushima was like a homecoming for me. It was my fifth consecutive year performing at the biggest arts festival in the world right here in my hometown. It was also a return to the stage after a year of political journalism. It was an opportunity to work once more with my old Scottish Youth Theatre comrade Jack Tarlton, now Joint Artistic Director at Presence. This was a partnership forged on giggling early-teen train journeys and in the unforgiving nature of Glasgow’s Old Athenaeum ‘gong show’ cabaret.

But Emperor Fukushima was also a return to the very subject which brought me to Scotland as a child. My fourth birthday in 1979 was spent on the road, literally, as my mother, Alison, walked from Gloucestershire to protest against the commissioning of Torness nuclear power station. Admittedly I spent much of the journey being pushed in a buggy. Torness was opened by Margaret Thatcher in 1988, the year Alison died. Swedish playwright Jacob Hirdwall’s Emperor Fukushima explores living with the consequences of nuclear power disasters, and the concept of legacy. Part of my mum’s legacy was to instil in me a recognition of the power of stories as an important part of how humans relate to the world. Hirdwall’s play also explores this, with the two characters relating personal experiences of two of the most famous disasters to hit nuclear power: a meltdown at Chernobyl in the Ukraine in 1986, and at Fukushima Daiichi in Japan in 2011, where the Tōhoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami led to nuclear meltdown. The play is unequivocal in its criticism of nuclear power, comparing it to an anthill poked with a stick by a child. Today, in the political maelstrom of balancing short-term emissions targets with the increasing appetite for endless energy consumption, nuclear power remains seductive for politicians. This is exactly the type of issue where the power of theatre is absolutely vital. It can step back and allow characters to ask the wider questions that journalists won’t. Questions which exist outside the current news cycle. Questions like how can burying lethal nuclear waste in bedrock be “guaranteed” to be safe for 100,000 years?, or how to make a warning sign understandable to a language not invented yet, but not so colourful it appeals to natural curiosity. The power of stories indeed. In Japan, earthquakes continue to cause concern for the Tokyo Electric Power Company. It hasn’t stopped Japan signing a memorandum of understanding with the UK Government to develop new capacity here, where there is little fear of earthquakes. Torness was initially given a lifespan of 35 years, but in February 2016 French operator EDF energy gave the place an extended lifespan. It will now operate until 2030. Only a month after the announcement a reactor was closed because of an undisclosed issue with a valve. In November seaweed caused another reactor closure after it interfered with a cooling water inlet. ‘The emperor is patient. He can wait.’

2 Comments

As part of Presence Theatre's Festival Season in 2016 Jack Tarlton held the Shakespeare workshops at the Deer Shed festival and the Green Gathering. Here he writes of the sometimes complicated relationship he has had with the playwright over the years. Many people must recognise loving someone but feeling that you are not good enough for them. I used to feel this way about William Shakespeare.

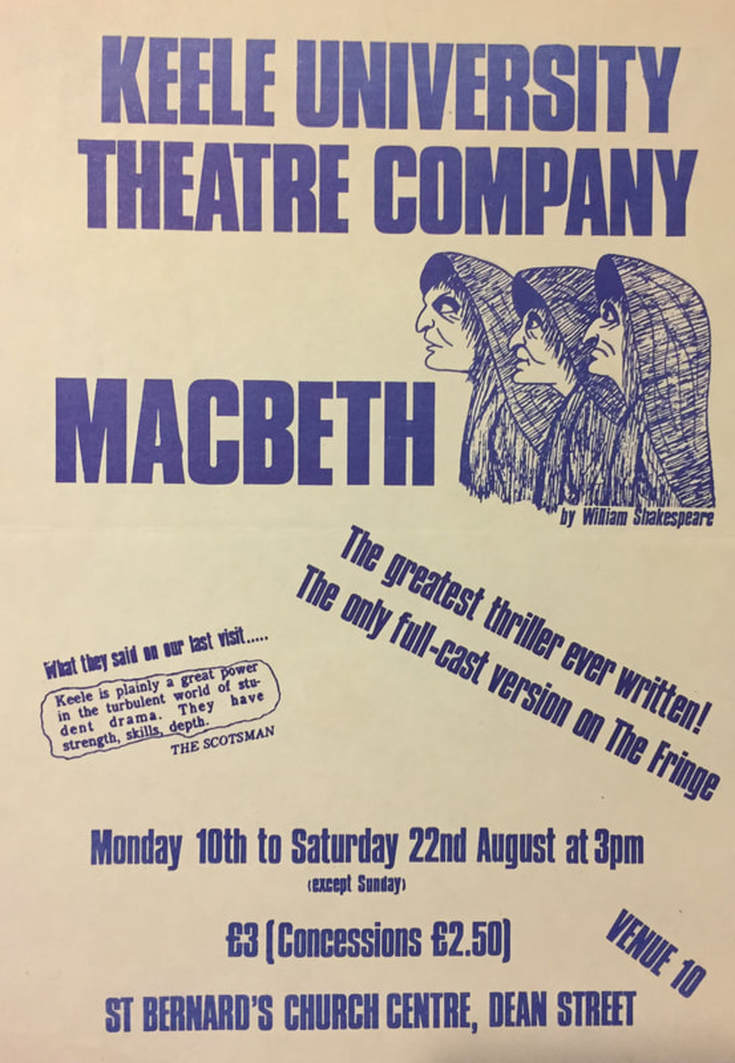

When I was eleven I played Son to MacDuff in a production of Macbeth by Keele University at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Not only did this mean afternoons off school hanging out with bearded, probably hung-over students and my first cup of instant coffee but I also got to be in a play with witches and swords and blood in which I thrown about the stage before being brutally slain. It was thrilling and this is what Shakespeare meant for me then and for many years to come – an intoxicating, transgressive, slightly dangerous world. But one that I did not fully understand. What I said and what was said to me on stage could be as obscure as the language back-stage, punctuated by what I realise now were code words arranged so that the rest of the cast could engage in their filthy student speak without offending my young ears. I can still clearly hear one of my lines spoken in my younger self’s voice – “With what I get I mean, and so do they.” I’m not sure I ever really understood what this relatively simple sentence meant, and it still strikes me as somewhat opaque, although with an attractive, seesawing rhythm that still feels good to say three decades on. Throughout my childhood I would avidly look forward to seeing a Shakespeare play and found them engaging, funny, sometimes really scary, but there would always be long passages that I found impenetrable and I would sit there waiting for the fighting to begin. And at the heart of it, it was because I didn’t understand what was being said. I could grasp snatches of dialogue and generally understand what was happening but it was as though the actors had not been properly tuned in. I could hear the individual words but often they were set in this great block of incomprehensibility. I still loved the sense of magic that was always somehow captured but when I thought of Shakespeare there remained a blank, a barrier. And it could feel like a failing on my part. But I kept digging in. I attended workshops in which the intricate world of his verse started to open up to me. I began to see that it existed almost as a physical entity, constructed with machine-like grace that could be pulled and pushed to make it work in many ways, with Shakespeare himself guiding you through. Three years at drama college and spasmodic sessions on Shakespeare and a wildly enjoyable second year A Midsummer Night’s Dream was soon followed by my first theatre job - playing Paris in Troilus and Cressida. By William Shakespeare. In Stratford Upon-Avon. With the Royal Shakespeare Company. It felt like I was trying to get with someone way out of my league in their hometown with the world watching. In rehearsals and on stage I was very exposed. I worked and worked but never quite found the fluidity that I was hoping for and that I could perceive in some of the other more experienced actors. “They’re just words” I remember our Troilus saying. And they are. And they aren’t. There is a formality to the structure of the verse that provides a strong, supple spine to help approach the words and the multitudes they contain, but I felt locked into it. I was adhering to a set of rules that I had learned at college but felt as though I was in subjugation to them. All rigour but little freedom. Some years later I got my second Shakespeare gig – Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet at Chichester Festival Theatre. I had the best time. One fantastic thing about the play is that is requires a young cast, the energy of which for that summer spilled out the rehearsal room to the pubs, parks and countryside around Chichester. And I got to get killed again, but this time not before a mighty sword fight with flying sabres which myself and Tybalt would practise in the sun outside the theatre at any opportunity. Especially whenever someone attractive walked by. There were still the words though. And quite a lot of words in a very famous speech packed with some of Shakespeare’s knottiest and most expressive writing. “O then I see Queen Mab hath been with you …” There can be the desire when approaching a well-known speech by Shakespeare to “do” something with it, to hurl yourself at it from a particular angle, to have worked out where you want to end up before embarking on it. I certainly approached the speech and by extension the character this way, and while I am still happy with some elements of my Mercutio it struck me then and now that it was a hard but blunt portrayal. I had made too many assumptions about him before rehearsals began and did not allow myself to make discoveries beat-by-beat, line-by-line, using the detailed clues that Shakespeare seeds throughout his plays for his fellow actors. Four years later I got to spend many months in his company when I was asked to join the all male acting troupe Propeller. It meant a return to Stratford with The Taming of the Shrew as part of the RSC’s Complete Works Festival, before rehearsing and opening Twelfth Night at the Old Vic in London and then taking both productions around the world. This tour was soon followed by another comprising The Merchant of Venice and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, meaning I found myself working, living and having adventures in Australia, Italy, Japan, Germany, Spain, Hong Kong, Ireland, Poland, New York and throughout the UK. Propeller’s studied yet irreverent approach to the text, music and staging stems greatly from so many of the actors having worked together for years on previous productions, meaning each had a strong familiarity to the cadences of the verse and prose and none of the fear of stepping up to and honouring the plays that I had had in the past. As a new-boy you quickly pick up this relaxed approach, the text one more element among many to make your own and play with. Although the relentless touring and lack of female energy on stage eventually made me decide to step-down from the company, I shall always remember my time with Propeller with great affection and as the time when Shakespeare’s world properly opened to me with a big welcoming cheeky grin. However, what has unequivocally made me fall in love with Shakespeare’s work has been teaching it. I have discovered that the time spent preparing and holding workshops has given me a deeper understanding of and appreciation of the extraordinary ways that he utilises language and in learning to communicate that to a group of students the joy and sense of shared humanity that it can bring. The first real test of whether I could teach Shakespeare was when I offered to hold a two hour workshop for students at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich when I was living there in the Autumn of 2010. Any nervousness that I felt at teaching students at a German university - having never gone to university myself and in their second language - was magnified by asking myself how do you actually teach it? I had gained more dexterity in my performances but how to impart that to others? I knew instinctively that I wanted to change the students’ perspectives - from that of reading his plays with an objective academic overview and instead to think of themselves as an actor living through the plays. Put simply, to make them stand up and speak the words aloud. As for the nuts and bolts of what to actually teach I returned to my copy of John Barton’s Playing Shakespeare that we had been encouraged to read at drama school and discovered that looking in detail at the ways the iambic pentameter is constructed and Shakespeare’s use of elision, onomatopoeia, caesura, alliteration, contrapuntal stress and antithesis provided me with a series of practical steps to take the students through. And I started to find exploring them as exciting and liberating as when I first learnt about the iambic pentameter as a teenager. The two-hour workshop evolved into a daylong and then a two-day session and I still return to Munich every summer to teach. I have subsequently taught Shakespeare Studies at East 15 Drama School and in 2015 I proposed to Presence that I could hold a number of Shakespeare workshops as part of our first Festival Season. One was picked up by the Northern Green Gathering and again by the larger Green Gathering in 2016 along with a Shakespearian Insults workshop that Deer Shed festival asked for to complement our Reading Group Live! event there, and which I was more than happy to create. These two workshops for last year’s Festival Season remain some of my favourite ever moments in my relationship with William Shakespeare. Whether it was enthusiastic children shouting “You bull’s-pizzle!” at each other in a packed tent in Yorkshire or the enquiry and commitment that festival-goers of all ages showed whilst battling against Hari Krishna chanting at the William Shakespeare: Actor & Playwright workshop at the Green Gathering, I was continually surprised and moved by how much other people are into him too. I found the greatest way to show my love for him was to share him, to watch him encourage others to throw themselves way out of their normal everyday comfort zones to create something of real spontaneity and brilliance. Not once in my time working with them and watching the scenes that the participants created did I feel that sudden dread of not understanding what was being said, instead I followed every word perfectly and laughed and applauded when the others did. Unfettered by the actors desire of having to get it right, or to do something with it, this was Shakespeare being met in the most spirited and democratic way possible, making his speeches, characters and scenes genuinely come alive. A few weeks ago I was invited to join the Lamb Players in their yearly Shakespeare production in the garden of Lamb House in Rye. Four days to rehearse and tech All's Well That End's Well. Quite a few lines to learn before rehearsals with the crack team of actors began. We all stepped up to the challenge and the required instinct and appetite for adventure made me think not only of how it must have been for Shakespeare's original actors but also of last year's Festival Season. I am indebted to Deer Shed and the Gathering Gathering for taking the risk and commissioning the workshops and to all those who came along for bringing me to a place where I no longer feel any inadequacy in my long relationship with my old friend William Shakespeare. Because no one who took part in either workshop displayed any shred of it. They went in trusting their love would be requited. With special thanks to my Festival collaborators Beth Chalmers and Jamie de Courcey. Playwright Charlotte Keatley brought the latest draft of Émilie's Reason, her play based on the life of the 18th Century French polymath Émilie du Châtelet, to the Reading Group in June 2017. Here in an open letter to all who attended she writes of the energising symbiosis between playwright and actor. Fantastically helpful and invigorating to hear my current draft of my new play read in one energetic swoop by the Presence Reading Group. Although I always read my scenes aloud as I'm writing, it's obviously never the same as hearing other voices. I always try my play drafts aloud or on their feet with actors as I write drafts, in order to hear the real meaning and subtext (as opposed to what I think I'm writing ... my unconscious is always ahead of me). There's also the crafting: hearing the nuts and bolts of dialogue, images, rhythm and how they may need rewriting or cutting. With the Presence group, hearing my characters rotated around different readers was a great way to hear different dimensions of the characters.

The relationship between playwright and actor is for me the symbiotic heart of making good theatre. It never ceases to enthrall me how I can go over and over some words of mine, testing and questioning them, but it's only when an actor reads them in a way I never thought of doing - with an emphasis I never tried - that I suddenly hear what those words are for. That's the magic-seeming, collaborative complicity of playwright and actor. Sometimes in a reading, it can be the pauses or breaths an actor takes tell me how my play is working or not. Most of all, hearing my current draft read through without a break allowed me to get a detailed sense of how my new structure is working, or where I need to cut and move scenes, or insert something else ... I often workshop my plays, but invariably there's a pause in a play-reading after some scenes, and people want to talk. Hearing the whole arc with the Reading Group showed me the energy of the play as it is at the moment and as it would reach an audience. My thanks to every person who read, and listened, and laughed, sighed, gasped, or gave me that silence of when we are collectively moved by something. I'd love to come back with another draft of this or another play to try with you. Most of all you gave me more encouragement than you can realise by turning up, and giving your enthusiastic responses. So much of playwriting is (for me) about enduring loneliness, confusion, and my sense of failing, though there are of course those good days when I the writing is singing. Finally getting to work with actors is the reward. Presence Theatre enthusiastically crossed onto the mainland European stage for the first time when Colin Ellwood and Simon Usher took part in the Dreams Before Dawn Festival in Paris, a few days after the Brexit vote that saw Britain start to retreat back across the threshold. Here Colin writes of their experience exploring the work two British writers, Robert Holman and William Shakespeare, in a truly international context. Ten days after the Euro referendum in July, and Presence is crossing a border that suddenly feels a little more substantive. It’s as if a string has snapped and we’ve all been propelled into a more consequent and weighted reality, holding our breath to a drum roll of uncertainty and a vague sense of borrowed time. But then maybe that’s just being over-dramatic. It remains to be seen what any decoupling might actually entail. Either way what we are about to embark on feels very timely.

I am due to meet Simon Usher at St Pancras Eurostar terminal on Friday late afternoon. We are going to be spending the weekend running workshops as guests of the Dreams Before Dawn Festival of English–speaking theatre at the Theatre De Menilmontant in Paris. An event organized by my good friend and colleague from Rose Bruford, Matthieu Bellon. For the second year in succession he’s drawing a small flotilla of largely experimental performances from budding companies across the channel to glitter and bob for a whole week in the 20th arrondissement, near Pere Lachaise. We’re there to feed into this with workshops on Shakespeare and France, and on the plays of Robert Holman. The former is an obvious offering perhaps although we think we have an interesting angle to pursue. It’s also great to have the prospect of exploring the latter’s work in the context of a culture that might really value its quiet intensity, moral seriousness, boldness and individuality: qualities that in Robert’s work are nonetheless anchored in a richly evoked and very English sense of place. The perfect combination we hope for our aims here. Our whole enterprise really begins the day before departure, on the Thursday afternoon in – appropriately enough - a small French café on Richmond High Street, meeting Robert who has generously agreed to let us film a conversation with him. It’s a very hot day, but cool in the slightly echo-ey, shaded interior. After establishing whom the workshop will be for – largely students, young directors and performers is our guess – Robert begins by denying any ability to talk meaningfully or conceptually about his work. For the next hour though he is delightful and absorbing company: thoughtful, exploratory and engaged, all these qualities spiced by a determined vigilance against easy over-explicitness. Simon sets the tempo, playing the diligent, careful sapper, mining foundations while I occasionally intervene rather opportunistically. Robert weighs words, measuring and maintaining distance, easing in and out of intimacy. He is a man for specifics, for the emergent rather than the imposed. It’s a broad-ranging discussion, much more so than can be done justice to here – the following being merely a flavour. Very early on in the conversation Robert acknowledges his absorption in character as a factor central to his work, and we tentatively point to the recurring in his plays of central figures reaching out from isolated interior worlds, searching perhaps for vicarious experience: ‘I never thought of that. People looking for others who will give them security’. The figure of a handicapped girl in a hospital cafeteria, self-enclosed but somehow contentedly absorbed in life, features in Robert’s most recent play A Breakfast of Eels, perhaps, suggests Simon, admiring this quiet directness, as a corrective against self-pity in others. By way of what is perhaps a contrasting example but directed to the same end, I recall that Neil in the much earlier Rafts and Dreams has escaped from horrific child abuse to train as a doctor, but can’t in the end quite complete the journey into ongoing daily practice. He commits suicide. ‘Neil’s tragedy is of not being able to be a different person’ says Robert ‘I’ve written the same play over and over again I know that … about having the courage to learn from experience.’ How did he come upon the extraordinary central image of Rafts and Dreams in which the living room of the protagonists becoming a raft floating between continents as a great flood inundates the world? He says that at around the time he wrote it – 1990 - he realized he wasn’t going to be a directly political writer in the way of (his examples) an Edgar or Hare - so decided he might as well ‘do what I wanted’. Setting aside the subsequent currency of the threat of global flooding, the idea of Robert as ever having considered his work political in that direct, assertive, conscious way is a surprise. But on the other hand, in terms of politics as a matter of ethics: Robert reminds us he is from a family of Quakers, his father and grandfather conscientious objectors in consecutive world wars. His father shortly before he died told him that if he had known before the war what was to ensue, he might have fought. He points out that the existence or otherwise of evil is a focus of several of his plays. However he also offers a corrective to such abstract considerations: ‘The idea is to be not aware at all just write the next line’ Family is acknowledged as both a central concern and a resource. In the very last speech of Rafts and Dreams, 14-year-old Alex remembers returning from a school trip: ‘Coming home, my parents were there, and I absolutely surprised myself by rushing straight into their arms. That was it, that's all it was, I was home.’ ‘That speech is true’ says Robert, It’s a beguilingly simple formulation that he uses twice in the conversation, the other being in relation to the handicapped girl. In that instance he means that he witnessed a version of the scene, sitting in the café of a London hospital, absorbing, observing. With Alex, the connection seems more personal, more direct. Then a further reflection: ‘All plays fail. There is an innocence in Alex – Neil [who kills himself] can't deal with the innocence of Alex – I could have got that better now, made it clearer’ His says his writing has in recent years has become more collaborative. ‘I’ve always remembered actors in the theatre: Gielgud and Richardson in No Mans Land; Penelope Wilton at the Donmar. I’m interested in actors….and I’ve always said there’s no point in writing unless you enjoy your own company, your own loneliness even, and I think I now enjoy that less.’ As a consequence certain actors have become collaborators, sharing their own experiences as stimulus and material, and even on occasion choosing character names. He needs, he says actors with a weight, a low centre of gravity, who will stand still on stage and not move. ‘My plays are still’. His most recent play, A Breakfast of Eels, was apparently difficult to place in theatres. ‘I don’t do as I’m told’. But having said this he characteristically tacks back, remembering occasions watching his own plays in performance ‘where I can’t be bothered either. I know why you don’t like it. Plays are about energy; people need to reciprocate’. His plays of course multiply replay that effort. After the difficulty he found in writing Eels outside any relationship with a particular theatre, he wanted to write a long letter to Rufus Norris looking for a home for his next play. Fellow playwright David Eldridge, a good friend, sometime collaborator and great admirer of his work advised instead a short, direct email. The resulting commission was immediately forthcoming and this evening he’s off to see Beggars Opera at the National in the version by another self-confessed Holman admirer – as well as friend and collaborator – Simon Stephens. For someone who seems very much an individual, self-contained, he is discretely but deservedly well-connected and cherished. ‘I’ve learnt something over the years – I don’t know what’ It’s all great material for our purposes. We’ll show the film (taken rather shakily on my laptop) at the workshop on Robert’s work on Sunday morning. The following afternoon Simon and I converge again at the St Pancras Eurostar terminal. In keeping with the odd atmosphere of that post-referendum moment, someone is belting out an unintentionally Les Dawson version of Rule Brittania on one of the battered pianos that leaven the surrounding cosmopolitan blandness. We spend our time on the train reading for our first workshop in Saturday morning, both regretting not having had more time and enjoying this rather wonderful chance to concentrate on Shakespeare. We arrive at a rough format for the following mornings workshop, the topic of which is to be Shakespeare and France. We want to avoid the obvious Henry V and VI stuff and focus on the France of the comedies, and as it impinges on other plays such as Hamlet – a France much less marked out as the enemy, but rather characterized as a slightly rarified place of fantasy and formality…almost a cross between wonderland and Arcadia, shading – in Hamlet and at times in for example All’s Well - into something darker. A mere three hours after setting off, we are arriving at the flat we are to stay in is in the 4th floor of a rather stylish 50’s block in the Rue Des Prairies about 20 minutes walk from the theatre. It’s a beautifully ordered, dignified and rather decorous place: Dark wood furniture, art books on immaculate shelves. We can only guess at the identity of the owner who has so generously made it available – and thank both them and Matthieu and his family for having organized our use of it. Rue Des Prairies sounds very ‘epic’. Prairies in such an urban setting makes me think of Brecht’s Jungle of the Cities … and a subsequent internet search turns up a 1950’s Jean Gabin film named after the street set at the time of its post-war brave-new-world construction, that seems to focus on a family not dissimilar to the one in Brecht’s play. But that’s all by the by. The epic-ness now seems a quirk, an anachronism throwing its current air into relief. Now it seems beguilingly tranquil and anonymous, dormant, biding its time silently - at least at weekends. In the morning, refreshed, we find a café and finalise the preparation work we started on the train. We arrive at the theatre a little early and sit in the cool, airy foyer to meet Matthieu and Amanda Collins, who with her customary assiduous tact has been helping organize events. Apparently people will join us from a yoga class currently taking place so in the meantime we are given a tour. The Menilmontant complex turns out to be three performance spaces and several rehearsal rooms in the shell of an old abbey – all beautifully maintained. Seeing this it’s easy to recall the rather depressing air of neglect of equivalent semi-municipal institutions in London, that exist like beached flotsam from a much more communitarian age. The adjacent school playground injects a further subliminal soundtrack of youth and optimism. On the tour we bump into a small group of would-be participants hurrying in, worried about being late, a hearteningly international group: A couple of Brazilian students and Victor a teacher from New York. By 11 o’clock there are around fifteen people present – Irish, Brazilian, Polish, UK, US, Icelandic. We all get into the main theatre space with its huge stage that opens out onto what is to all intents and purposes a sunlit patio. The chairs are pushed back and I introduce a couple of limbering exercises and then Simon launches in, first with a tag game and then some exercises of possessing and communication fragments of Shakespeare text, here from Miranda in The Tempest. ‘Oh I have suffered/with those that I saw suffer’ A participant is drawn into the centre of the circle to more fully attempt the speech. Simon’s intermittent, insistent demand to ‘shift’ seems to unbalance the participant into direct unmediated and instinctive response. The concentration around the group seems total … and there seems a general delight in this testing. Later, turning to Hamlet, we collectively discover a verbally ‘stabbing’, pugnacious and explicitly-Danish Claudius, against a mellifluent, urbane and ‘Frenchified’ Laertes. Simon make the point that Laertes implicitly self-claimed ‘Frenchness’ accords with other instances of the ‘idea’ of Frenchness around in England at the time ... denoting an interest in form, in abstractions and surfaces: ‘a very formal Frenchman.’ And there we have to halt – we’ve already gone well beyond our allotted finishing time of 1pm. Our shorter afternoon session is billed as a discussion on French influence on English theatre, but interest in this morning’s work is strong and it is decided we will continue with that work. So after a lunch al fresco at a nearby café we reassemble to focus on the Princess’s final speech of Love’s Labours Lost, with its demand that ideas and verbal formulations be tested against that most primal and empirical of experiences - death. Such is the general absorption we never quite get to our third and fourth examples, centring around Jaques’s Montaigne-like playfulness and skepticism in As You Like It and the nostalgic almost Proustian world of All’s Well That Ends Well. This afternoon session is more reflective than the morning had been, but seems well received, and for the rest of the day we graze in the sunshine in and around the theatre, stepping into the cool darkness intermittently to see the three short performances curated by Bred in the Bone, Matthieu Bellon’s organizing collective. These are basically Shakespeare ‘mash-ups’ of Hamlet, Macbeth and Lear reconfigured around women protagonists and in entirely re-imagined scenarios. It’s a huge and bold range of work distilled in roughly 20-minute blasts. Given any knowledge of the plays, the resultant redeploying of individual fragments of text can be disconcerting (not necessarily a bad effect). The highlight is undoubtedly the Lear, performed with simplicity and clarity almost as a Beckettian ‘Not-I’ monologue albeit in a post-Hurricane Katrina family setting. The following morning we are sad to leave ‘our’ flat for the last time, but console ourselves with coffee and croissants in one of the cafés that already feel a little like second homes, as we prepare for the Holman workshop in the afternoon When we arrive at the theatre we first watch the half-hour film Matthieu’s brother has made of the latter’s rehearsal of a Bred in the Bone version of Don Quixote in a Kent barn the previous summer using Shakespeare text. It’s an account of what was clearly an extraordinarily intense exercise, and maybe also a corrective to our speculative focus this weekend on the formal, abstract linguistic burden of French culture [as, admittedly perceived by the English]. In the film, young performers give their all, generating emotion from the Shakespeare text, trying almost to chase their own tails. It’s both wonderful and at times agonising to watch. It’s the exploring of a kind of Shakespearean underbelly, and, I speculate, perhaps Matthieu’s own reaction against the received cultural formality of his homeland. The Holman workshop seems a perfect conclusion to our contribution over the weekend – a gentle and forensic exploration of extracts in the shadowed and cool rehearsal room. It’s great having Victor the New Yorker there, since his engagement seems to cast yet another set of national characteristics into the mix, bringing into focus the restraint and obliqueness of some of Robert’s characters in contrast to Victor’s brilliant effusiveness. Of the four plays we intend to look at in the two hours, we really manage only one in any depth: Making Noise Quietly. We look at the opening two pages and it’s a delight rediscovering the poise and restraint of its dialogue and its sparseness and boldness in slowly building a tacit and unacknowledged relationship between two characters from entirely contrasting backgrounds. Their finding of an undemonstrative, shared intimacy – beautifully and ambiguously balanced between assertion and denial - seems like a perfect emblem of the cross-cultural connectedness we are attempting here, and of the festival as a whole. It also perhaps serves as antidote to the sentiments behind the defiant Rule Brittania from the St Pancras piano. Yet again the intimacy and particularity of a play by Robert seems to offer a resonance with more directly ‘political’ concerns, all the more effectively so for being so rooted in a specific dramatic moment and world. We end with the film of Thursday’s Robert interview, and leave people intrigued and keen to find out more. And that’s it ... Final food in a conveniently adjacent café, then we return to the theatre for the closing of the festival and a short heartfelt speech from the main stage by Matthieu to a weary but satisfied contingent of around 30 participants that are still around, many of whom have weathered the full week. There is a sense of attainment in the air, of experiences that will be remembered for a very long time. Our taxi to the station is slightly delayed by the tightening of traffic as Paris hunkers down for the final of the Euros at the Stade de France. A sudden flourishing of blue shirts on the streets and cries of ‘Allez les Bleus’ from the pillions of passing motorcycles. We are well beyond the Channel Tunnel when word filters through of the slow draining of French hopes. It’s been an illuminating weekend and one perhaps offering a sense that nationalities have a salience best savoured in their mutual exchange and presence rather than in their separation ... Stephanie Rutherford was new to Presence Theatre when she was approached about participating in the double-bill of Now That's What I Call Music and The Frugal Horn at Backwell Festival. But after reading the scripts she soon found herself embarking on a series of journeys on her way towards the final performance and beyond. All aboard the beloved south-eastern to Herne Hill, for my first experience with Presence Theatre. Some weeks prior I had skyped a Mr Tarlton about a forthcoming project that required a flugelhorn player. There were two plays: The Frugal Horn by Nick Payne and Now That's What I Call Music by David Watson, that the company had discovered and decided to put on as a rehearsed reading at the Backwell Festival. The plays made for a good read so here I was sipping tea in Herne Hill before a rehearsal of the rehearsed reading. Once everyone had arrived and after the anticipated meet and greet chats we formed a circle and started to read. After discovering what was actually going on and discussing characters, we put it on its feet to give it shape and looked at establishing certain moments more in depth.

Now That's What I Call Music is a fast-paced, energetic ensemble piece that speaks directly to the audience. A record company have just listened to a demo and are now projecting their professional opinion. They constantly attack and overlap one another with positive contradictions. The rhythm of the language speaks as music in itself. In perfect contrast The Frugal Horn is a beautifully honest story of a young girl's journey to finding her lost flugelhorn. She travels to parts of the country she has never seen before and interacts with people from different walks of life. With each encounter she develops confidence and comes closer to getting her hands back on her flugelhorn. However when she finally does, she is asked to play it, which afterwards contributes to her decisions to leave the instrument with its final owner. This is a delicate play about what is not said and honours the inner desires and sometimes painful complexity of human nature. The audience come to realise the flugelhorn is much more than just an instrument, to Alice it signifies her late father. So this is also a journey through grief to acceptance. A week later we all met again outside a petrol station in Hammersmith, piled into a car and hit the road toward Bristol for the Backwell Festival. I didn't quite know what to expect when I got there but I wasn't disappointed! A small village had created a contagiously fun environment full of world music, tasty food, and copious amounts of glitter. There was a fabulous community vibe to the day with people of all ages enjoying what was on offer. We performed our plays in the cosy but packed literature tent to a generous audience. We had so much fun together in Backwell that we didn't want to leave at the end of the day, but alas the lengthy car journey back to London was calling, so so after a celebratory beer or two (for those not driving!) we said our goodbyes and hit the road once again sharing our car games. It has to be said, when I was first asked to be a part of this all I knew was that I enjoyed reading the plays so joined forces and went along with it. What I was not expecting was to end up loving the plays, to have two fun days out and to work with a group of such passionate, enthusiastic and downright lovely people. So thank-you Jack, Helen, the other Jack, Tom, James, Beth and everyone else who was a part of making it all possible and getting these two wonderful plays to new ears. In June 2016 Artistic Associate Caitlin McLeod joined Simon Usher and Jack Tarlton at the Nottingham Playhouse for a new experiment as part of the Nottingham European Arts and Theatre Festival. Would Presence Theatre's Reading Group work with an audience? And could the spontaneity and sense of "unknowing" lead the actors, directors and audience to instinctively commune more deeply with the plays themselves? No one knew what would happen. There really wasn't any way to get prepared. In fact, the only option was to throw caution to the wind and just see where the moments led you.

This, of course, was the first ever Presence Theatre Reading Group Live!, but it was also a philosophy we came to understand, when reading Jon Fosse aloud. Simon Usher explained to the acting ensemble (a terrific troupe of performers, mostly local, all superb) and the audience, that Fosse doesn't do well with a huge about of colour, lots of emotion, any preconceptions. In fact if you try too hard to make emotional and narrative sense of his writing, it just doesn't work. It starts to clog and jar against what is so intriguing in his plays: characters and their circumstances, seemingly simple and mundane, are often walking an extreme tightrope between life and death. His writing starts to make sense only when you let go and let it lead you. You can't force it somewhere meaningful and complex, it has to take you there. We had to adopt this philosophy pretty quickly with the Reading Group Live! because we genuinely had no idea what would come out the other side, but for me, it is a wonderful way to think about approaching text and performance. The idea we did have, was to kick off the afternoon with our actors taking turns to read short plays by European playwrights. After the first few we would invite audience members to come down and populate a few empty seats and have a go with us. Of course there's always the possibility with these events that no one will budge from their seats. But the risk factor added spice to our day. And the unique attribute of the Reading Group is in fact this element of spice: no one knows exactly what will happen. We all discover the work together, here, now. It's a rare moment of true collective experience that we strive for in theatre, on the stage. And it's often extremely hard to manufacture. You have to trust the writing, and embrace the risk. During our afternoon at the Nottingham European Arts and Theatre Festival (neat16), we were rewarded by doing just that. Some of the best moments we witnessed, and the keenest discoveries about the Norweigan writer's work, along with our playwrights from Russia and Catalonia, Mikhail Durnenkov and Esteve Soler, came from hearing unsuspecting audience members, brave enough to come join our half moon of actors and directors, simply read the words cold. That's when they really began to sing. These non-performers brought only themselves and their curiosity, which turns out to be a whole lot. It's a good lesson for us directors and actors: often the less you bring to a text, the more you find. Each of the short pieces brought to neat16 held a similar, and surprisingly powerful colour. They were dark with only shards of light, they were often extremely absurd in theme and narrative and there was a certain sparseness to the form and the dialogue which resulted in a huge amount of comedy. The audience responded warmly, embracing each of the pieces with gusto and it became clear to us that they felt this kind of absurd, sparse, dark writing mirrored they way we are all experiencing the world today. It felt truthful, human, profound. It felt real. Collectively, we left the Nottingham Playhouse with a few new philosophies to practise: prepare less, let go more, accept the absurdity of our world, and you'll enjoy where it takes you. Artistic Associate Colin Ellwood writes of introducing plays by Ramón del Valle-Inclán and Edward Bond to Presence's September Reading Group and of the echoes and parallels found there and in earlier work discovered within the circle of chairs. A rich, absorbing and substantive Presence Reading Group session last Friday 30th September at our usual venue Calder Bookshop Theatre attended by some regular readers, a very welcome newcomer, and industry guests.

In the morning the great Spanish ‘surrealist/slash/realist’ Ramón del Valle-Inclán’s ‘Esperpento’ tragedy Bohemian Lights traced the nocturnal journey of an impoverished blind poet through the dangerous and politically-contested streets of 1930’s Madrid, in desperate search for a missing lucky lottery ticket; eliciting some very deft and insightful in-the-moment characterisations from the group. It rapidly became clear where a good proportion of recent Spanish drama finds its inspiration: Valle-Inclán is revered in Spain, much less well known in the UK. A couple of session back the group tackled the Russian pre-revolution symbolist Aleksandr Blok’s The Stranger, and there seemed to be in Bohemian Lights something of the same spirit, crash-landed here into a recognisably realist world of big-city small-hours vividness: One example of the resonances, connections and comparisons across texts and cultures that the Reading Group can uncover. In the afternoon: a key component of Edward Bond’s sometime brawl with Shakespeare: his Lear from 1971. This Lear is obsessed with the building of a wall to keep enemies out, and Cordelia here leads a Maoist counter-revolution [more Bernie Sanders than Hillary, then]. Lear is befriended by the ghost of a gravedigger’s murdered son who becomes progressively more vestigial and agonised as public atrocities mount. There are so many things that could be said about this extraordinary work: it’s a stark, sharp-etched autopsy on the mechanisms and implications of social violence, through which clarifying, elliptical images and parables bubble like water through desert sand: ‘the giant must stand on his toes to prove he’s tall’. The shade of Valle-Inclán’s blind poet, ‘a mannered Andalusian; a poet of odes and madrigals with a classical blind head; a wandering philosopher with a spectral presence’ falls suddenly across the face of the mad-sane new-blind king…. each wandering their respective heaths, mythical or urban, real or imagined. The intended appetisers: short duologues and ‘eclogues’ by New York Beat poet Frank O’Hara will have to wait…… Presence Reading Group sessions, held usually on the last Friday of each month, offer actors and invited guests the chance to explore, share and voice a range of scripts new, neglected and undiscovered; contemporary and historical; both in translation and from the domestic repertoire. Everyone present participates in the voicing of each play, so there is no separate ‘audience’, and the aim is always to share roles on an equal basis. No preparation is required: discovery in the moment is all. After every play, a brief discussion airs responses before we move on. A great way to discover new repertoire, develop sight-reading skills and to share a passion for great drama and rich language. Artistic Associate and "new boy" Colin Ellwood pulls back the curtain on Presence Theatre's Reading Group to reveal the hidden treasures beyond on the day that Simon Stephens brought Country Music to the group. Just prior to 11 o’clock, a slow gathering outside on the pavement and a brief confusion over access. Among those to roll up is special guest Simon Stephens, one of whose early plays is to be read. Entrance effected, we insinuate ourselves into the depths. This slightly mysterious establishment always reminds me of Steppenwolf; or of Verloc’s shop in Conrad’s Secret Agent; or the bowler-hatted Mr Benn’s 70’s T.V. emporium of trans-historical psychedelia. Transit through a mysterious curtain is involved here too, on the way to the small basement’s surprisingly accommodating windowless grey void.

It feels like an almost illicit pleasure to be sharing this experience with fellow sufferers of whatever need or appetite draws us in against the grain of the more noisome prevailing cultural tides. Here, refreshingly, there is no pitching for parts nor rehearsal claims being staked. Our presence is devoid of pretext and so feels like a tacit and slightly scary admission of interest in the thing itself, whatever that might be: Maybe a ‘being’, a simple attentiveness; a present-ness sufficient to and inflected by the skein of words soon to be threading between us; an unforced Quakerish-ness; a (literal) ‘amateurishness’ that in an increasingly ‘professionalised’ world is surely the beating heart of all who truly profess. Today as always, an initial air of benevolent transgression prevails, a sense of mildly dissident possibility, as well as a delicious day-beginning dreaminess, the metaphorical soft-fuzz on the un-squeezed peach of expectation (the prospect of a language-fix occasionally over-stimulates the organ of metaphor….) We sit in a round, maybe 12 of us, a pleasing variety of ages and genders. There is amongst the men a preponderance of trilbies (disappointingly not bowlers) that vanish as people settle. The piano is not to be played, costing extra according to the attached notice, and the prohibition fires a terrible unspoken temptation, barely but impressively resisted. Having been both puzzled and moved by Caryl Churchill’s Escaped Alone at the Royal Court the evening before, our arraying here to me recalls that play’s core accommodation: random chairs gathered together in anticipation of small gifts of attentiveness in the context of larger disturbances over which we have no control; fragments gathered and offered against our collective distrait….Auden’s ‘small ironic points of light’…. Presence is surely a beautiful name for a theatre company: The very sound of the word somehow evoking a release of pneumatic pressure, a leaking from the individual into the oceanic. Of course presence comes in different intensities and types. Here is not the lumbering, over-earnest, individualist kind sometimes striven for in readings but rather, in the main, presence fleet, exploratory, provisional, interactive and insightful; redolent of confidence, awareness and ease. The presence of the plays, the texts, draws out the presence of the readers as a group as much as individually. For those attending, such presence is two-fold: potential and kinetic, with no absolute boundary between the two, and the former slipping easily and speculatively into the latter; with the resultant ‘present’ materialization of the play being a slow accretion of these multiple individual ‘kinetic’ offerings, unforced and (in every sense) un-forged; each one as if effecting a ‘passage through’ some small but vital door, opening into yet another hidden passageway along which the ‘real’ play must secretly pass. Over the course of the day the thought frequently occurs that here I am amongst accomplished experts, truly, but above all expert in exploring; essaying now in the nets rather than on the field; curious, where curiosity has only its own stakes and rewards, and open to the discovery of new mechanisms: waiting, searching for and alive to the clicks of multiple and serial locks being sprung (all plays have a kind of individual lock-mechanism, surely). Proceedings are convened today by Joint Artistic Director Jack Tarlton, than whom it would be impossible to imagine a more sensitively attentive host, and here operating as the ever-adaptive facilitator, floating expertly like Ali’s butterfly. Simon Usher – fellow (and originating) Joint Artistic Director – complements as the more oracular bee-stinging still-point. Together they are wave and particle; the Goldberg and McCann of what proves to be a very gentle play-interrogation process. I am the new boy (this my third of these more-or-less monthly events) already mildly addicted. We begin with Simon Stephens’ Country Music. As is the custom in these parts, roles are re-distributed (here by Simon Usher) scene-by-scene, with what appears to be an initial loose awareness of conventional casting suitability. Participants are asked not to read the plays in advance, so to encourage freshness of discovery, response and adaptation. This is the acting equivalent of fly-by-wire with the text as the cockpit radar signal, and readers simultaneously responding and expressing; constantly recalibrating their offerings in a creative feedback loop. It’s a joy listening to each contributor home onto the text’s emerging signal, sometimes elegantly ‘back-flipping’ or neatly u-turning as some crucial aspect of character or dramaturgy becomes apparent; ruthlessly burning off earlier attempts in the ongoing mapping of what works, is true and resonates. Such recalibrations warrant here no shrug or other tacit admission of ‘error’: everyone present understands that a preliminary bold choice primes for its better-targeted replacement. As someone who has over the last couple of sessions found myself occasionally administering roles, I am aware that this is done best as if through half-closed eyes, in a mild panic, from the hip, with an awareness of the importance of as many people as possible participating, yet also wary of unduly fragmenting the play; so taking advantage of natural resolutions and breaks in the writing to shift roles around the group. Simon U seems to start here quite ‘conventionally’ – ‘yes such-and-such could play that part’ – and that is in itself often (and certainly here) a revelation: participants seem suddenly to shed a skin, to develop a concentration and unselfconsciousness in the offering and creative varying of versions of themselves that have not quite been previously legible in their charmingly unassuming social personas. As time goes on Simon U's distribution of roles proceeds as it were deeper into the group, and perhaps this is where some of the richest revelations come: richest because in some ways least expected. What might initially seem slightly implausible castings begin to reveal a deeper compatibility, offer new perspectives. Country Music turns out to be an extraordinary series of surgical strikes, an exercise in consecutive and ruthless dramaturgical keyhole surgery: A whole generational saga, life story, articulated and anatomized through four ruthlessly-sunk bore-hole scenes, each a single, intricate and sparely-written duologue anatomising the central character’s slow crumple from exuberant Don Quixote to bewildered Sancho Panza, over some 30 years. A life-tragedy in four strokes, four agonizing striations, caught with the compassion and big-heartedness of a Dickens operating within the formal control of Webern; and with the central, initiating and explicatory encounter, the Rosebud keystone – devastating in the irony of its possibility – accommodated last: its high-octane ‘everything-possible’ teen-spirit revealed as the secret fuel firing every subsequent disastrous choice the protagonist makes. It’s the perfect reading-group play: all gesture, no cumbersome scaffolding: a Boyle Family recreation evoking whole landscapes of loss. Simon Stephens watches each contributor intently as they speak, angular like a half-unfolded heron caught between drowse, intense inquisitiveness and what looks like moderate surprise; or like a fond parent savouring the half-recognised, half discovered emergence of a favoured child’s long-suspected talent; quietly willing the revelations to keep coming. He is a benevolent magnet gently drawing forth the performances like iron filings; recognition and discovery fused in one cherishing, inviting physical ideogram. I’ve never seen anything quite like it, and as someone who attempts sometimes to help young directors develop, this immediately becomes my model for the appropriate directorial attitude for the willed ‘drawing forth’ of actorly extrusions. Simon S is of course as if born to test the descriptive limits of words like ‘rangy’; ‘lope’ and ‘bounce’; built as if for traversing long-distances on foot, he has the speculative angularity of a high-jumper addressing a bar set to new personal best. All chairs seem slightly too small for Simon the human question mark, yet he folds himself into even the most unpromising of them – as here – like some complex and expensively telescopic surgical instrument being returned to its contracted state; or as the elegant wording of an international treaty might address some contentious and intractable issue, assuaging all awkwardness and tension in the deft inclusiveness of its accomplished gesture. The reading of Country Music invites in my mind comparison with the rather approximately anthemic production of his Herons, recently at the Lyric, a potent but slightly cloth-eared production that seemed bent on realising the specifics of the play as rhetorical generalities; reimagining its unplugged granularity as stadium rock. It is a broadly effective strategy, bold and at times hugely exciting, but yielding results that are……well…..approximate, and – arguably – sentimental in the treatment of antagonist Scott, who is given a Willem Defoe Platoon moment of wrecked transfiguration, in the process wrenching the play from the central Billy and over-egging the already very clearly-etched social context for his borderline psychopathy. Scott is clearly the incipient artist in this production, a provocative situationist with a Fassbinder fascination for manikins and manipulation; a smudged Egon Schiele channelling Johnny Rotten and Malcolm McLaren while oozing otherness like primal spoor. By contrast the supposedly artistic Billy here circumambulates with the very worldly but thwarted air of a slightly bemused stockbroker whose car has broken down in a dodgy area. Billy nice-but-dim seems barely to have any connection with his journal-cum-sketchbook, supposedly the umbilicus mundi of a richly notated future. And he doesn’t fish. Overall, then, that production doesn’t so much tinker with the delicate mechanism of the play as paint it over. An unnecessary loss, surely, and one not characteristic of the equally bold but extremely ‘etched’, imaginative and large-gestured work of Ostermeier and Nubling from which it clearly draws inspiration. Boldness surely need not be at the expense of interactional precision; the needle can and must surely remain sharply in contact with the groove, all else being mere variety of amplification; optics magnifying the originating flame (many varieties and emphases of which optics/amplifications are of course possible, but only if the originating signal is sharp and true). And at the centre of any true signal is of course silence. In Country Music silence resides in the beautiful soul of Jamie, whereas in Herons it lives in the water and its wildlife, in the notebook and imagination of Billy, and in the unspoken regard between him and his dad. All these things are surely in essence the same. Despite its limitations, and from beneath its excitedly-applied daubs of Jackson-Pollock spatter, the Lyric’s Herons seems now to call out to its younger sibling, here being read in this Waterloo basement, and whose intricate mechanism emerges now naked and exposed. Some of the same concerns and configurations of Herons are visible here, re-arranged in a deeper and more sharply realized way. This is the play where Billy/Jamie shoots and avenges rather than absolves; the one that is justly centred around the ‘Scott’ figure rather than Billy. That rearrangement and re-engagement is surely a symptom not of the absence of invention but its deepening. Stephens like all very good writers surely heads continually towards the sound of his own gunfire; wrestles serially like Jacob with his own reconfigured angels and demons… After the reading a brief group discussion offers insight and immediacy, with a fascinating series of exchanges between the two Simons in particular. Then Simon S talks a little about the play’s inception; he tells a story about a performance turning a hostile and antagonized prison audience around. On the face of it this might be exactly the kind of ‘theatrical’ story it would normally be possible to be deeply skeptical about, but having just experienced the play’s combination of hard-nosed realism and big-heartedness, it seems impossible to doubt it. A further telling memory: When in the prison performance the daughter refuses to pretend any bond with her prison-estranged father, apparently there were shouts of ‘bitch’ from the audience, reassuring as signals of engagement yet depressing in the attitude revealed. The women in the play are clearly the real heroes…searingly brave in their sensitive but ultimately fruitless promotion of unpalatable but potentially therapeutic realities. Also revealed is that the playwright’s only recent contact with this unexpectedly and intricately lyrical of English pastorals (In which a Ballard-ian concrete mega-polis is imbued with an almost Houseman-esque numinousness) has been in German. Such are the travails of the globally-networked artist, such networks being of course the source of more recent Stephens angel-wrestlng and gunfire-chasing. Discoveries in the reading too: with the central character being read by three different actors in the three different timescales, whereas in the original production one actor remained throughout. The separation seems to fully embrace the devastating dislocations of the boy’s journey and personality, while allowing the more fundamental continuities to stand out with devastating clarity. And it’s only 11:30…. Top photo: John Seaman. A mother and father are grieving for the loss of their son Gustav, whom they presume to be dead. Until one day there is a knock at the door and there he is. Their son has returned and daily life is restored, but events soon twist wildly out of control as what seemed to be a bleak tragedy transforms into a brilliant black farce.

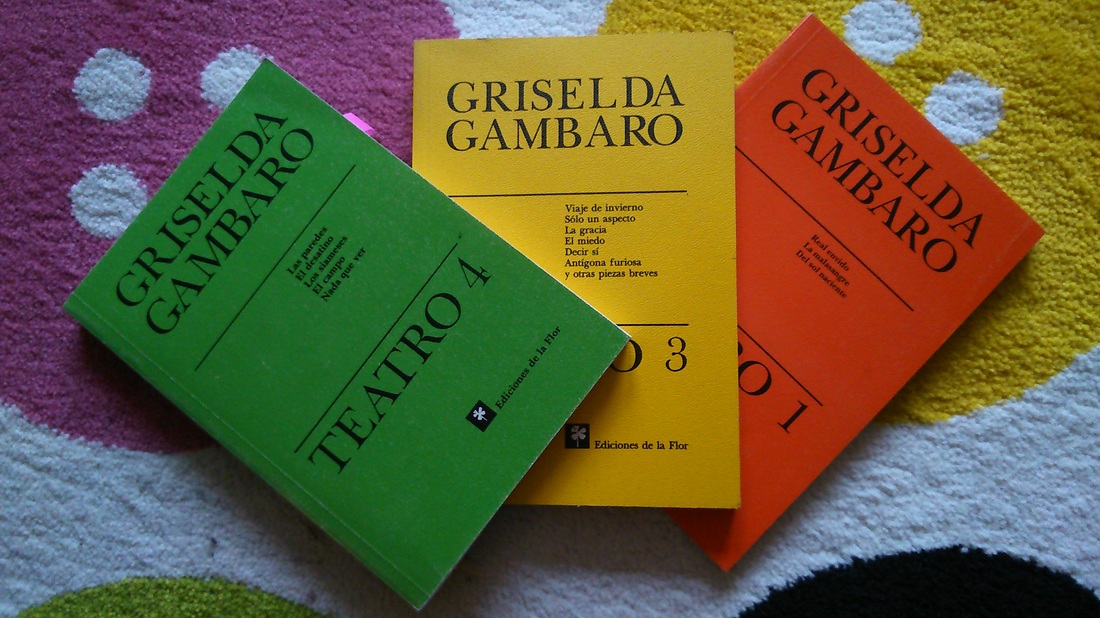

Fredrik Brattberg is an award winning Norwegian playwright with a background in classical music composition. His work has been performed in Norway, France, Denmark, Indonesia and New York. In 2012 he won the Ibsen Award for The Returnings. 4th March 2016 - The Norwegian Embassy An evening hosted by the Norwegian Embassy in London showcasing The Returnings to an invited audience. Cast: Emma Cunniffe, Kieron Jecchinis & Adam Newington 18th September 2015 - Nordic Drama Now at the Free Word Centre An afternoon of performance and discussion at the Free Word Centre in London around recent developments in contemporary drama from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden that included a staged reading of The Returnings. Cast: Emma Cunniffe, Bill Nash & Adam Newington 11th July 2015 - Backwell Festival With The Returnings Presence Theatre helped launch the Literature Tent at Backwell Festival, a much-loved independent festival in an idyllic setting offering an inspirational and eclectic line-up of music, dance, art, food and workshops. "The Returnings is unsettling, thrilling and funny. With delicacy and wit it examines grief – our obligations to the dead and how to honour them – and asks uncomfortable questions about our selfishness in the face of responsibility." John Donnelly, Playwright "The highly talented cast enthralled the audience, drawing out emotional responses at every twist and turn ... an exceptional 35 minutes of theatre ... the accolades were flowing - ”Brilliant” “Exceptional” “Enthralling” - we knew we had witnessed something very, very special." Jane Sabherwal, Backwell Festival. Writer Gwen MacKeith joined the Presence Theatre Reading Group in May and November of 2015. Here she responds to the insight gained by hearing her translations of Griselda Gambaro's work read aloud for the first time. I have participated twice in the Presence Theatre Reading Group. On both occasions I brought translations of plays by the acclaimed Argentine dramatist, Griselda Gambaro (1928-). Though one of the most celebrated living writers in Argentina, and a playwright of international standing, she is nevertheless little performed on the English-speaking stage. This special forum is a natural home to explore her theatre.

For several of the actors present, this was their first encounter with Griselda Gambaro and yet the group collectively attuned to her texts in ways I found exhilarating. This is one of those rare opportunities to see the first creative impulses of skilled actors at work; the freshness of that first response to a text, 'the choices conscious and unconscious' as actor Siubhan Harrison puts it. Those first impulses can often be the right ones, as I so often experience as a translator when I return to the first words I chose in an early draft, after developing a translation for some time. It was also a liberation for there to be no particular preconceptions of 'Argentine-ness' in this context, as rather than illuminating Gambaro's texts, this can often serve to block insight. The works we have read together are from very different periods: Los siameses / Siamese Twins (1967), Sucede lo que pasa / Whatever Happens Happens (1976), De profesión maternal / Mother by Trade (1997), and Pedir demasiado / Asking Too Much (2001). To hear the plays read in quick succession was an interesting thing in itself, as it allowed for observations about the development of Gambaro's corpus over the many years she has been a practising dramatist (Gambaro began writing for the theatre in the mid 60s and continues to stage new works, the most recent being El don performed this year.) The readings, orchestrated and conducted by Jack Tarlton, are referred to by the group as 'sight readings', and this analogy with music is apt. To treat the text as a musical score avoids the deadening effect of getting bogged down by meaning. All the actors share reading parts in the script and this creates multi-layered interpretations of the plays, as the characters are inhabited by the different voices of the actors present. When the Reading Group met in May, Gambaro was read alongside two fascinating young playwrights: Hannah Moscovitch (Canadian) and Nis-Momme Stockmann (German). Coincidentally all three dramatists shared a black humour which dared us to laugh at the bleakest of human experience: child abuse, domestic violence, mental illness and dementia. Gambaro's invitation to engage in black comedy is fundamental to her drama, and it was heartening to witness this invitation being so creatively accepted by the Reading Group. Of course, on hearing a script read it becomes evident what doesn't work about a translation, as well as offering new revelations about the play itself. I began to see things, through the voices of the actors, which I had not perceived before. I have a conviction about the quality and significance of Gambaro's theatre. I greatly admire her unsqueamish gaze as she probes the thorniest and most indigestible of human emotions: cruelty, guilt, shame. The atmosphere of daring created by the Presence Theatre Reading Group is a fine laboratory in which to experiment with her plays in English. Here I found a rare tolerance for the ambiguity that is pivotal to Gambaro's drama. There is an inferred world in her plays, 'a shadow world' as Simon Usher described it. Of course, the great hope is that these readings will lead to other things: full productions offering the recognition in the UK that Gambaro deserves. And yet these meetings are significant happenings in themselves. I found myself moved in ways I did not expect, knowing the plays as well as I do. This is both testament to the depth of Gambaro as a dramatist, and the work of those actors who lent their imaginations and their voices for a day to bring her plays to life. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed